I need to tell you about a conversation I had with my 4-year old daughter this morning. You’re going to have to stick with me, because despite the potty talk this is going somewhere, I promise. The backstory is that lately she’s been forgetting to wipe after going to the bathroom (this is the type of stuff you’re here to read, right?). So when she got up this morning, this happened:

Me: “Did you go to the bathroom?”

Her: “Yes.”

Me: “Did you wipe?”

Her: “Oh… no. I don’t think so…”

After a few seconds of silence, she said something that’s pretty obvious, but hasn’t occurred to me before as the cause of the problem:

Her: “The toilet paper is behind me so I forget. We should put it in front of me so I can see it.”

Well, of course. Mystery solved. See, a few weeks ago I accidentally broke our toilet roll holder (yes, I’m pretty sure this is the kind of thing you come here to read…), and since then, we’ve been putting the toilet roll on the back of the toilet. And that was the cause of my daughter’s sudden “forgetfulness” in the wiping department.

This immediately made me think of product design, and in particular, the all-important principle of recognition vs. recall:

Showing users things they can recognize improves usability over needing to recall items from scratch because the extra context helps users retrieve information from memory.

It also reminded me of a great story Marco Arment once told in Right versus pragmatic. You should read the whole thing, but the gist is that at a previous job people kept dropping trash at the door before they left the bathroom (what is it with me and bathrooms today?), despite increasingly passive aggressive signs being put up by “management” to please throw trash in the bins. Here’s Marco’s illustration of the problem:

Source: Marco Arment

The solution that worked in the end? Put the trash can by the door. Seems obvious, but it still took them quite a while to figure it out. Instead of trying to change behavior — or to get people to remember to do something they’re not used to — they put a trash can where people are already throwing stuff, and that solved the problem.

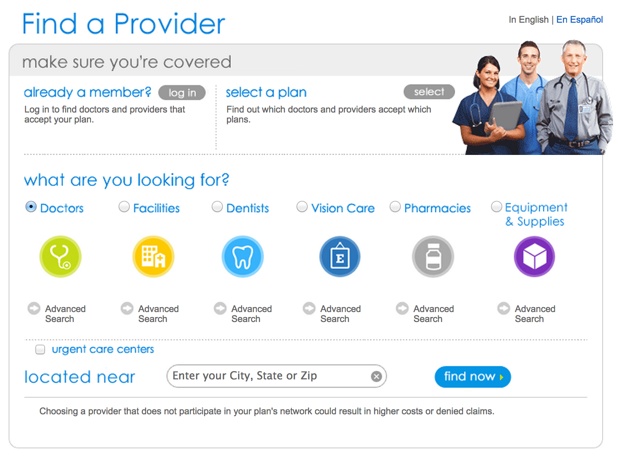

Ok, enough with the bathroom examples. I recently had a discussion with a health plan who has a tool for their members to find doctors who are in their network. They mentioned that they get a lot of customer service calls from users who complain that they can’t search by a doctor’s name. This frustrates the health plan because the interface clearly lets you do that. But when you look at the interface you can see why they are having this problem. Here’s the home page:

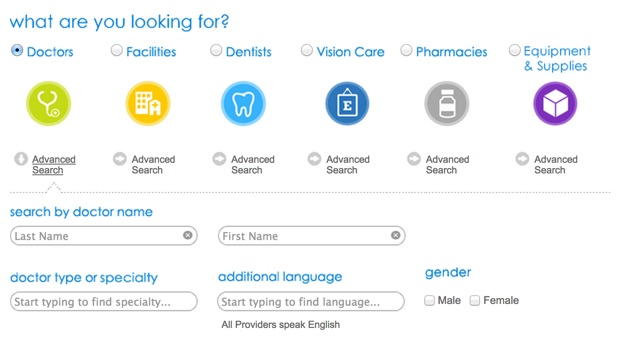

Can you see where to go to search for a doctor by name? Not sure if you guessed it, but you have to click on the “Advanced Search” link under the Doctors icon:

Here’s the point of all this. Just because a feature is in the interface, it doesn’t mean users will find it. Just because an option is in a menu, it doesn’t mean users will know how to access it. And just because the toilet paper is somewhere in the bathroom, it doesn’t mean my daughter is going to find it.

The lesson is pretty simple, but there are enough everyday examples out there that it’s something we should continue to remind ourselves of. The next time you design an interface, say this to yourself over and over: If I want people to use toilet paper, I should put it where they can see it.