This post is sponsored by Rackspace Digital, the digital marketing infrastructure specialists.

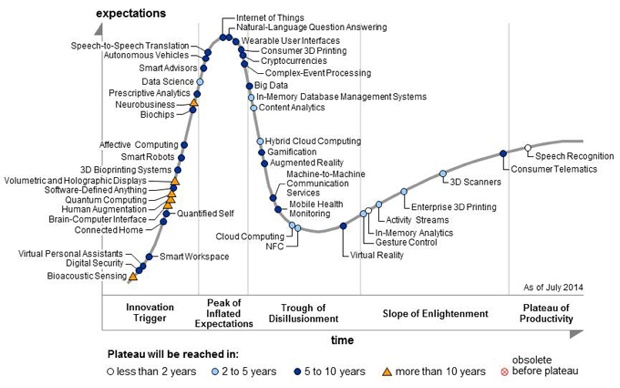

In recent months, wearable tech has shown signs of emerging maturity. Not only are wearable devices getting smarter and more powerful, they’re also becoming more practical and beautiful. As batteries and sensors continue to get smaller, and with Google releasing the Android Wear operating system back in March, a slew of new wearables will hit the market before the end of the year. Smart watches, glasses, shoes, shirts, even jewelry. According to ABI Research, 90 million wearable devices will ship before the end of 2014. Here are a few of the new arrivals.

Riding Big Waves and Big Data

Rip Curl, an Australian company and an iconic brand in surf wear, is currently trialing its own smart watch with 200 surfers around the globe. Some surfers, like zealous runners, want to track all their stats—from the number of rides to top speeds, miles paddled and time spent in the water. Due to hit stores mid-September, the GPSSearch will be the world’s first GPS-powered surf watch. It uses satellite positioning and other sensors to obtain data and measurements that are then processed in the cloud using a cutting-edge database service. All the user information can be synced to an iPhone, iPad or desktop for visual analysis.

Google Maps in Your Shoes

Indian startup Ducere Technologies is launching a pair of “smartshoes” known as Lechal shoes. The shoes connect to your smartphone with Bluetooth, using vibrations and Google maps to alert you when you need to make a turn. The left or right shoe vibrates depending on which way you need to turn. Not only is this a boon for runners or walkers in an unfamiliar city, it also has big payoffs for the visually impaired. Reportedly, Lechal shoes have already received 25,000 orders, even though the company won’t make them available until the end of the year. The shoes will cost between $100 and $150.

Making the Wearable More Wearable_

While Under Armour and Omsignal are leading the way with making smart shirts with built-in sensors for tracking workout data, there’s a new plan to take over the rest of your wardrobe. Ministry of Supply has launched a new line of men’s dress shirts using the same technology that NASA has implemented in its spacesuits for temperature regulation. The shirt absorbs heat when you’re hot and releases it back when the temperature dips. The good news is that it looks like a real shirt, not a space shirt.

Wearable Experiments, meanwhile, has released the Navigate Jacket for both men and women. A companion smartphone app stores destinations and feeds them to your jacket, turn by turn. LEDs and vibrations on the sleeves ensure you never make a wrong turn.

And finally, if vibrating jackets aren’t your style, consider the latest in wearable tech from Cuff, a manufacturer of smart jewelry. Now available for pre-order, the bracelets, necklaces and key chains come in a variety of styles and finishes that look more like accessories than tech hardware. Each piece of jewelry uses a small component called a CuffLinc that acts as an alert system. Using Bluetooth technology, the CuffLinc will sync up with a smartphone app to handle alerts and push notifications that can be customized for a personal network of friends and family.