The biggest problem that many Mac users struggle with is that we work for organizations that use Exchange for email and calendar management. This means that, in most cases, we have to use Outlook for Mac if we want the majority of basic tasks to work. It’s an application that is so ugly and bug-ridden that most people look like this every time they open it:

The problem is that traditionally it’s been pretty difficult to make OS X’s Mail.app play well enough with Exchange to be a viable replacement. For my personal use case there were a few things that always held me back:

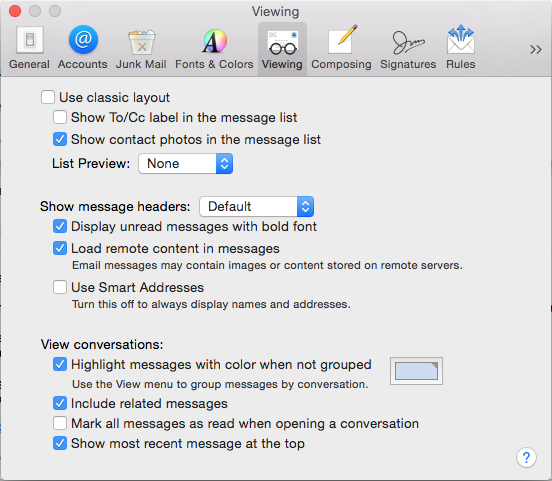

- The default view settings are not conducive to effectively manage a lot of email.

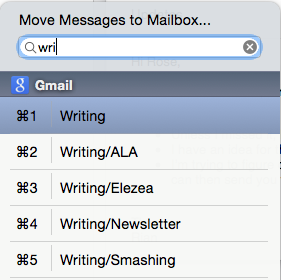

- No keyboard shortcuts to move messages into folders.

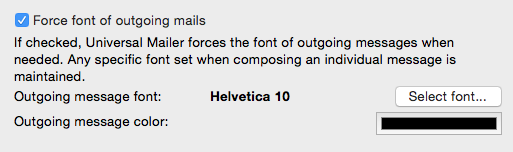

- All other email programs display the default system font when it receives an email generated in Mail.app — in Office for Windows this is Times New Roman.

I think I’ve finally addressed these issues enough to make Mail.app my primary mail application and ditch the horrors of Outlook. But you’ll need a few settings and plugins to get that done.

View options

I like the simple, friendly list view that these options give me. Try it out:

Shortcuts for moving messages

Mail Act-On 3 is an essential extension. It does a bunch of different things, but for the best feature is that you can map a key to moving messages to a different folder (I use “v” to match Gmail’s shortcuts), and then use type-ahead to pick the right folder:

Changing the default font

Universal Mailer is another powerful plugin that just makes Mail.app work better, but its best features is that you can set a system font that is respected by other email programs:

Unexpected bonus features

Switching to mail brings a bunch of great things with it that you don’t get in Outlook:

- Smart folders that can bring a bunch of different emails together based on specific criteria you set.

- Great integration with iOS, since it takes advantage of handoff.

- Fast email that’s not ugly.

All I’m saying is, give it a try. Your eyes will thank you.