As is often the case with these things, I just noticed two articles that make very similar points about the quantified self movement. In Quantify Thyself LM Sacasas makes the point that we don’t know what we don’t measure:

Not only do we tend to pay more attention to what we can measure, we begin to care more about what can measure. Perhaps that is because measurement affords us a degree of ostensible control over whatever it is that we are able to measure. It makes self-improvement tangible and manageable, but it does so, in part, by a reduction of the self to those dimensions that register on whatever tool or device we happen to be using to take our measure.

In a similar vein, Anne Helen Petersen has a great piece on Buzzfeed called Big Mother Is Watching You: The Track-Everything Revolution Is Here Whether You Want It Or Not. Here’s the kicker:

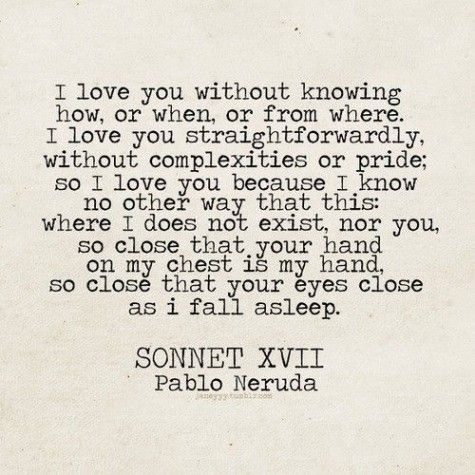

But there’s something to be said for the allure and beauty of the mysteries not only of our confusing, previously unknowable bodies, but the intricacies of life. For the daily banalities of tuning the thermostat, or of knowing you had a good night’s sleep because you feel good, not because an app indicated as much. For the pleasure of running without knowing how fast or how long or how many calories but simply because your body could and did move, and that even without a digital trace, a GPS footprint, or way to leverage evidence thereof against friends and co-workers — it nonetheless felt something like being alive.