Over the past few months I have become fascinated by what I like to call “crazy-busy PM” thinking in the product management world. I’m sure you’ve seen a few tweets or articles about this yourself, but here’s a small sample, all from fairly big voices/blogs in the industry.

From 15 Things You Should Know About Product Managers:

It is common to go through the whole day as a PM, and get absolutely nothing done. Your calendar is stacked. The meetings are booked. There is a ton of talk, but nothing seems to have actually happened (outside of a bunch of new items for you to follow up on). Meanwhile your team is sitting there with important questions, you have two-hundred unanswered emails in your inbox, Slack is firing off notifications left and right, and you have a doctor’s appointment at 4:30pm you have to get to (because you’ve missed your appointment three times in a row). It is frenetic.

From The State of Product Leadership 2019:

The best PMs I know are crazy-busy humans who often seem caught in a precarious equilibrium between enthusiasm and frustration.

From Emotional Debt:

Being a product manager can be like riding a bike, except the bike is on fire – you’re on fire, everything is on fire. That’s how our days can feel. We have to take care of our product, our team, perhaps our finances. Our schedules are full from looking after other people or things. And these things invariably drive emotions; we care passionately about our products, we can love and loathe our stakeholders, and we feel an almost parental-like responsibility for our teams.

I think it’s time to have a real discussion about this, and the damage this kind of thinking is doing — not just to the individuals who work in such environments, but also the industry as a whole. In this article I’d like to discuss why I believe this is such harmful thinking, and what we — and you — as individual product managers can do about it.

Why “crazy-busy PM” thinking is harmful

First, it needs to be said that if your days are “frenetic” and “you’re on fire, everything is on fire,” you cannot possibly be doing your job well. That’s not my opinion, that’s just how your body works. There’s plenty of research and science around this, with the most succinct and relevant explanation probably being Cal Newport’s book Deep Work:

Then there’s the issue of cognitive capacity. Deep work is exhausting because it pushes you toward the limit of your abilities. Performance psychologists have extensively studied how much such efforts can be sustained by an individual in a given day. In their seminal paper on deliberate practice, Anders Ericsson and his collaborators survey these studies. They note that for someone new to such practice (citing, in particular, a child in the early stages of developing an expert-level skill), an hour a day is a reasonable limit. For those familiar with the rigors of such activities, the limit expands to something like four hours, but rarely more.

So the first thing to realize about “crazy-busy PM” thinking is that it is, quite literally, making you do sub-par work. In such environments you don’t have time or space to be thoughtful in your questions, feedback, and responses. So you are selling yourself short, first and foremost.

The second way this is harmful is to the future of the industry in general. Who in their right minds would look at a sentence like “it’s like riding a bike, except the bike is on fire – you’re on fire, everything is on fire” and go, “oh, that sounds great, sign me up.” How are we going to attract deep strategic thinkers to the role if that’s the expectation? We are doing the entire future of product management (and, not to be dramatic, but quality products in general) a disservice by perpetuating this myth that to be a good PM, you have to be a “crazy-busy human.”

How to be a more balanced product managers

If you are in a role like this, the first thing I want to say is that it doesn’t have to be this way. It’s possible to change your environment. The way I look at it, your personal workflow is a product just like any other product you’re managing. And if your product is dysfunctional, you have to prioritize making it better.

Let me be clear that I’m not saying product management isn’t a stressful job. I know that it is, and our ability to care deeply about what we make is an essential characteristic of the job. But the irony is that “crazy-busy” works directly against that care. So we have to change it.

How do we do that? By viewing your workday through the same lens you approach all your projects. If a project/feature is going off the rails, there are two, and only two options: increase the timeline, or reduce the scope. A “crazy-busy PM” lifestyle means you are off the rails, and you need to do one of those two things to get it back on track.

Increase the timeline

First, you can increase the timeline. Give yourself — and everyone else — more time to do the things they need to do. Argue for more realistic timelines. Explain how it will result in higher quality products and happier and more effective teams. I often find that teams run at the speed of the product manager. So this might be as simple as just you slowing down. The rest of the team will follow.

Reduce the scope

The other option is to reduce the scope of what you do. There are two primary ways I can see that happening.

First, delegate more of your tasks to the rest of the team. Do you collect all feature request? Set up a system for the team to submit them in a central place (we use productboard, but anything will do), and look at it at a designated time. Are you doing a bunch of first-line support? Great, keep doing that! But also get some developers involved. They’ll understand customers better and lighten your workload at the same time.

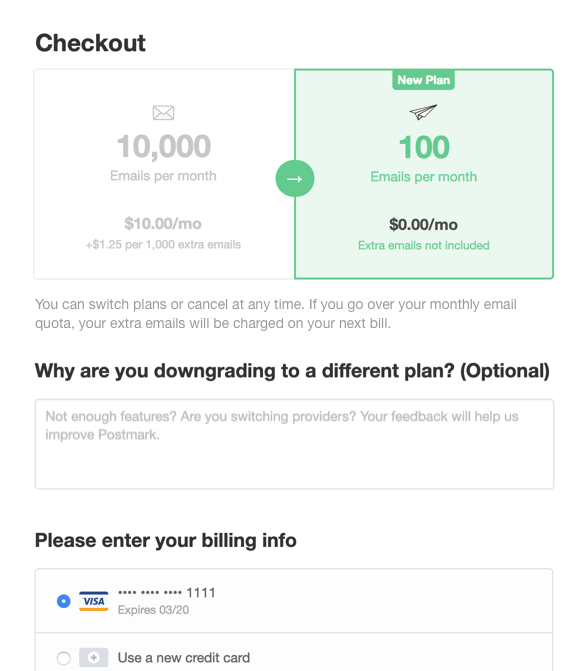

The point is to think about areas where you do all the work or where you’re a bottleneck and you don’t need to be. In our case at Postmark, I frequently got overwhelmed with spec writing. So we changed that. The lead designer/developer on a project now writes the first draft of the spec (we have a really nice template), and the rest of the team (including me) comes in afterward to ask questions and polish to the doc. The added benefit? Those team leads now have a way better understanding of the work they’re about to do, and they also feel a strong sense of ownership.

The second way to reduce scope is to split the product, and hire another PM. The best time to hire a new PM is just before they become “crazy-busy”. I want to reiterate that “crazy-busy” is not a sustainable position for a company to be in, and in these environments PMs will burn out (and do sub-par work while they’re at it). If none of the other things in these recommendations is an option where you work, you have to hire more PMs. Your company depends on it.

I understand the need for framing the PM role like it’s a constant rat race that no one except us understands. We want to feel like we do important work, and we want to be valuable to our companies. But I have to say, “crazy-busy PM” thinking is not the way to go about that.

We chose to do a job that requires a very particular set of skills, just like every other technology job. So, with apologies, I submit that we are not that special. The way to prove our value is to build amazing products that customers love. But that shouldn’t be our only metric. The safety, efficiency, and happiness of our teams (and ourselves) is an essential part of that. Let’s not kill ourselves in the name of good product. It’s not necessary, and in fact, it’s extremely counter-productive.

Update on April 21, 2019: Also check out the follow-up post where I share our template and answer a couple of questions I received about this article.