The Buzzfeed News article Behind Twitter’s Plan To Get People To Stop Yelling At Each Other is not the kind of thing I usually link to here, but I found it really fascinating from a product management perspective. Author Nicole Nguyen goes deep into the research and development process of the team responsible for “twttr” — an external, public prototype to experiment with new features. The sections that give us insight into the thinking of Sara Haider (Director of Product Management) and Lisa Ding (Senior Product Designer) are particularly interesting:

Haider and her twttr team are hoping to “nudge” people’s behavior in another way. Their hypothesis: Making the design for replies as minimal as possible, in addition to revealing how the conversation’s participants are related to you, may encourage people to read the entire back-and-forth before they react.

“We have this opportunity to learn about how not having likes and retweets could potentially change how people read things,” said senior product designer Lisa Ding. “Does it make you read something that you maybe would have guessed to be popular but actually isn’t that popular? How does that change the way you interact in a conversation? That’s super interesting.”

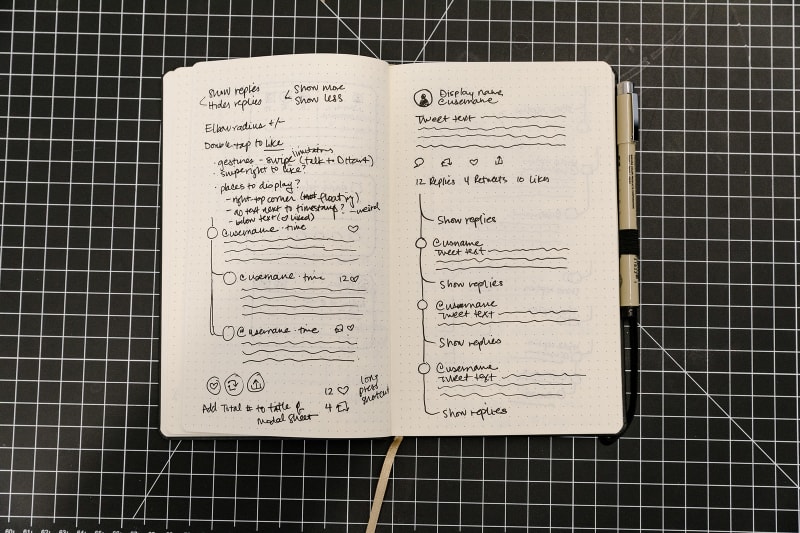

I also love Lisa’s sketches of the layout of twttr, and wish I could see more of that notebook!