My day didn’t start great. The first thing I read was Michael Dubakov’s statement about enterprise software people (i.e., people like me) in Enterprise software vendors have no taste:

My current theory is that enterprise software vendors have no taste. CEO, VP of development, Product managers that focus on enterprise market — all of them have no fucking taste. There is no taste in companies [sic] DNA, nobody cares about design and aesthetic. Profits, revenue, sales and new features — yes! Beautiful design — no.

Nobody, you guys. Literally nobody. I guess I don’t blame Michael for this false cause fallacy. It sure seems like a logical conclusion: product bad, therefore product person bad. As with most things, though, it’s more complicated than that.

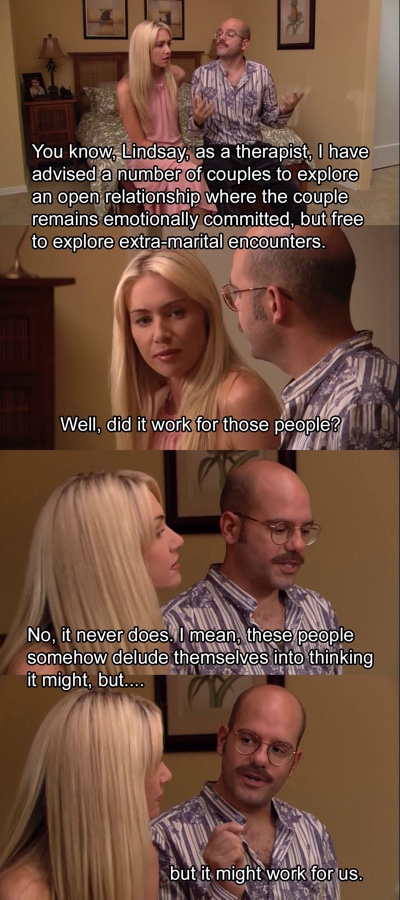

Let’s start with the most difficult thing about designing in the enterprise space: in most cases, the people who buy the software and the people who use the software are completely different, and therefore have completely different needs. This is not a problem in the consumer market, where the person who gives you money is usually also the person who uses your product.

The people who buy enterprise software — IT managers, HR managers, etc. — care about things like configurability, control, more features than a competitor, and most of all: the ability to customize the thing just so, so that it fits in with whatever systems already exist. End users care about none of those things. They care about getting a job done as quickly and with as much enjoyment as possible.

So, what happens is what happens in most organizations that rely on outside sales. Many Sales teams go out and sell things that don’t exist in the product. And they often sign contracts that have two things in it that make designers wake up in a cold sweat: (1) a list of features (or — ugh, I hate this term so much — “product requirements”), and (2) delivery dates.

Product people then have to fulfill the needs of the contract/promise (as opposed to the needs of end users) in never enough time. Instead of having the time to understand a problem and user needs, building hypotheses and testing them, and taking time to iterate, they make a thing to hit a deadline and then move on to the next thing that has a deadline.

And that’s why enterprise software looks the way it looks. It’s not that product people don’t have taste. It’s that they don’t have agency.

But, I do want to say, there are welcome signs that this is changing. There is a new realization that the needs of buyers and end users can co-exist peacefully, and the result is better products. As an example, our new CEO is a huge advocate for design, and is pushing the organization to create “simple, smart, beautiful products.” This will take time, of course, but if you look at the new suite of apps that we’re working on, you’ll see that these are starting to look more like consumer products.

There are other things I think we can do to help along this shift:

- Train sales teams on the ins and outs of product development. How prioritization works, how long things generally take, what the major user needs are that the product is trying to solve, etc. If they have more knowledge about how their promises affect the teams, it will go a long way to change behavior.

- Spend as much time with end users as possible, record the sessions, and share it widely. Nothing gets an organization riled up about good design like seeing end users struggle with a product.

- Start on a small product that no one cares about (like the mobile site maybe?). Follow a Lean UX process (or whatever methodology you subscribe to). Build it well, and show people the results. Then start moving the process into other areas.

So, anyway. Yeah, enterprise software is still, for the most part, pretty bad. It’s time for us to break out of the constraints of the past that caused that, and do something better. It’s actually a good time to be in enterprise software. There’s so much opportunity, and a newfound agency for designers. I’m optimistic. The day can only get better from here.