I am not qualified to talk about politics so don’t worry, I won’t. That said, Spencer Kornhaber’s essay on Beyoncé’s Radical Halftime Statement is so incredibly good (and very applicable to product design) that it’s worth discussing here. The part that I found particularly interesting is how differently Beyoncé and Coldplay view their “target markets”. Beyoncé is very focused:

But in pop and in politics, “everyone” is a loaded term. Stars as ubiquitous as Beyoncé have haters, the “albino alligators” who “Formation” informs us she twirls upon. And in a more general historical sense, “everyone” can be a dangerous illusion that elevates one point of view as universal while minimizing others. Beyoncé gets all of this, it seems. As a pop star, she surely wants to have as broad a reach as possible. But as an artist, she has a specific message, born of a specific experience, meaningful to specific people. Rather than pretend otherwise, she’s going to make art about the tension implied by this dynamic. She’s going to show up to Super Bowl with a phalanx of women dressed as Black Panthers.

Whereas Beyoncé is very specific about who her music is for (and not for), Coldplay tries to please everyone:

The poor guys of Coldplay, meanwhile, actually think they can work solely at the level of the universal. “Wherever you are, we’re in this together,” Chris Martin cried out, early on, last night. I don’t want to diss that intention, nor the take-home message at the end: “Believe in Love.” But from their first hit, “Yellow,” to their recent Holi-appropriating music video with Beyoncé, to their pan-cultural rainbow rally at Levi’s Stadium last night, their theme has only been about love to the extent that it’s been about how everyone loves colors. It’s music about being awed by the blandest kind of harmony: ROYGBIV, yeah yeah yeah!

Coldplay’s approach reminds me of this classic Sharp Suits poster:

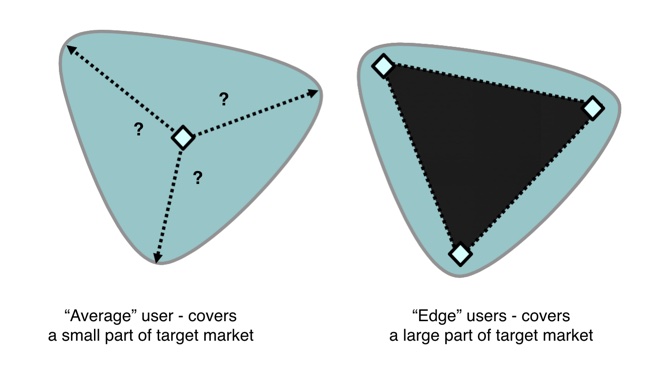

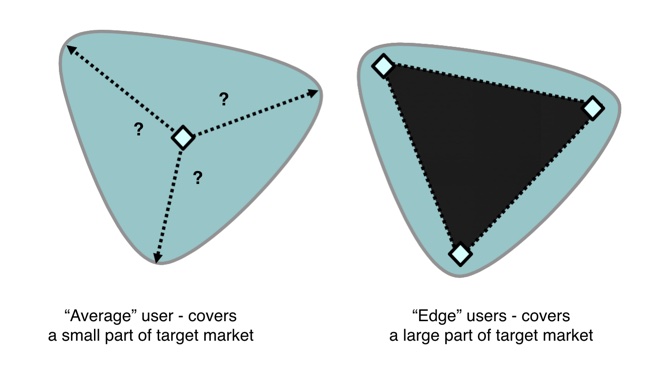

The problem with a target market of literally everyone is that you end up with a heavily compromised experience that appeals only to the very few people who identify with the “average” experience. Bringing this back to product design, this is why I’m still such a big fan of design personas. As opposed to a mythical “average” user, personas are solid people we can imagine using our product to achieve their goals. This is helpful because by focusing on a few different individuals that are closer to the edges of an experience, instead of the average, we end up catering for a larger portion of the user base:

This is what Beyoncé does so well. She makes music at the edges, so it’s exciting and anything but bland. It’s a lesson that Coldplay clearly hasn’t learned yet.