The traditional way of building software focused on requirements, driven by a competitive view of the market, and responded to perceived needs with additional features and functions. Our new way of developing products focuses on people first: on spending lots of time with them in order to build an almost intuitive sense for their emotional journey. We design with that journey and those emotions in mind, and as a result, we can produce great products that people love.

—Jon Kolko, Understanding our product design strategy and ecosystem.

New e-book: Practical User Research for Enterprise UX

I worked with the wonderful folks at UXPin to write a short e-book on how to overcome some of the challenges of doing user research in large organizations. From the introduction:

Once a company grows over a certain size, the internal politics and number of people involved in every decision increase so much that it becomes virtually impossible to stay focused on fulfilling user needs and business goals. Instead, the focus turns inward to the opinions and whims of individuals inside the company. Add the complexity of designing B2B products to the mix and, well, things go bad very quickly.

When an abundance of stakeholders are involved in a product, user research is the only way to focus a whole team on the real needs and goals required for success. It’s also the only way to get people out of the habit of thinking “Well, I want this, so everyone else must want it too”—a view that I find much more common in enterprises than in smaller organizations.

If that sounds familiar to you, you’ll hopefully find the e-book useful. I discuss why it’s often so hard to get support for user research in enterprises. Then I provide some advice on how to sell the value of user research. Finally, I offer some practical tips for addressing the subtle differences of conducting research in larger organizations with users who aren’t buyers.

You can download the (free) e-book here: Practical User Research for Enterprise UX.

Why everyone should do usability testing (even you)

I vividly remember the first usability test I attended. I was a brand new employee at eBay, and I walked into a dark observation room with no idea what to expect. I came out of that room 60 minutes later with the strangest mix of emotions—heartbroken that our product clearly had usability issues that made users incredibly frustrated, but also relieved and excited that we now had the information we needed to fix those issues. I became a usability testing convert for life, and have been making it a part of my product design process ever since.

I’m deeply passionate about this methodology and how it makes us better designers (and improves the experiences of our users), so I don’t think it should be something that we reserve only for the “highly trained” to do. Usability testing is something all of us should do as a regular part of our design process. But that doesn’t mean it’s straight-forward—there are many pitfalls and ways to generate bad data with usability testing. So I wanted to write a brief introduction to the methodology and why it’s so important, as a foundation for people who haven’t had training in the method but would like to make it part of their process1.

So, let’s start at the beginning.

Usability testing is a very powerful (and shamefully underused) user research methodology—when it is used correctly. In fact, usability testing is probably the only method that can be relied on to consistently produce measurable improvements to the usability of a product. Bruce Tognazzini once said:

Iterative design, with its repeating cycle of design and testing, is the only validated methodology in existence that will consistently produce successful results. If you don’t have user-testing as an integral part of your design process you are going to throw buckets of money down the drain.

But that all depends on the all-important “when it is used correctly” caveat. To make sure we do that, we need to understand when to do usability testing, and what to use it for.

When to do usability testing

To answer the “when” question I need to bring back the three buckets of user research I first discussed in Making It Right:

- Exploratory Research is used before a product is designed, to uncover unmet user needs and make it easier to get to product-market fit. Ethnography and contextual inquiries are the most-used methods in this bucket.

- Design Research helps to develop and refine product ideas that come out of the user needs analysis. Methods include traditional usability testing, RITE testing (rapid iterative testing and evaluation), and even quantitative methods like eye tracking.

- Assessment research helps us figure out if the changes we’ve made actually improved the product, or if we’re just spinning our wheels for nothing.

Usability testing is best used during the design research phase of a product. Ideally you’ll have an interactive prototype or some other lightweight interface to work with. It needs to be detailed enough to make sense to a user, but not so detailed that you’re reluctant to make changes based on feedback. Of course, you can also do usability testing on an existing live product, as long as the team has an appetite to make changes based on the insights that come back.

Usability testing shines during the design research phase since it plays on its strengths as a way to uncover the issues with an existing product or prototype. Trying to shoehorn usability testing into one of the other user research phases leads to trouble, since the nature of the data you get from it simply won’t help you make good decisions (i.e., don’t use it to try to decide what products to build, or if something you built objectively improved user satisfaction).

What to use usability testing for

This leads into what usability testing is good at: refining a product. It’s not good at finding out what to build (unless it’s combined with an ethnographic component). To put a finer point on what usability testing is most useful for, here’s a much-simplified diagram to put it in context with some other research methods.

We use methods like analytics and surveys to understand what happens in the product. We use analytics to figure what users do, and we use surveys or other interview techniques to figure out what they say about the experience. The problem is that this doesn’t help us understand why something happens, and without that information we won’t be able to fix any of the problems we come across. That’s where usability testing comes in.

What makes usability testing so perfect for understanding the issues with an interface is that it is an observational research method. It’s not about asking people what they think about an interface. It’s about showing them an interface, giving them tasks to do in that interface, and then watching them as they go through those tasks. We can ask them questions about the experience, but that’s just to provide context.

At its core, usability testing means that we observe users as they make their way around an interface, and use that data to understand what issues we need to fix. So, for example, if we see in our analytics that there is a large drop-off in our checkout flow, usability testing can help us figure out why that drop-off happens, and how to fix it.

Haters gonna stop hating

I’ve seen usability testing abused in several ways that have ended up giving it a bad name in some circles. Here are some guidelines to keep in mind to help break through those prejudices.

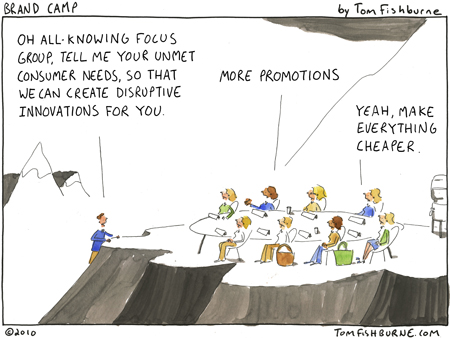

First, don’t confuse usability testing with focus groups. They are very different methodologies, and they are certainly not interchangeable. Focus groups are good for some marketing purposes—to understand brand sentiment or positioning. It is a terrible way to get feedback on an interface. Usability testing is so good at what it does precisely because it is a 1:1 methodology. There is no groupthink, no way to get influenced by other users. In that sense, it is controlled environment. Focus groups are anything but.

Second, remember the golden rule that usability testing is about observation. It can’t tell you which interface people like more than another, so don’t try to use it to settle those disputes. It’s the wrong question to answer anyway. It doesn’t matter what users like—it matters what they can use effectively to accomplish their goals. So usability testing is not “lightweight A/B testing”, as I’ve heard it described. It is meant to be part of an ongoing iterative design process with the goal of improving the product incrementally.

Finally, remember that you don’t need to be in a large organization or have tons of money to do usability testing. This is a methodology that scales really well. For startups who just have an afternoon to get some feedback, you can take some paper prototypes to a coffee shop. For large companies who need to convince a bunch of stakeholders to make changes, you can run a series of formal usability testing sessions. Whatever works—and don’t be mistaken, every little bit helps.

Go and make it so

I want to end this introduction with a small call to arms. Usability testing is an inherently uncomfortable methodology because it assumes and embraces the fact that your product isn’t perfect. That’s a difficult thing to make peace with—especially as a designer. But taking that position is the only way your product is going to get better. You can’t fix something that you don’t think is broken. Clayton Christensen made a similar point in The Innovator’s Dilemma. He calls this mindset “discovery-based planning”:

Discovery-based planning suggests that managers assume that forecasts are wrong, rather than right, and that the strategy they have chosen to pursue may likewise be wrong.

Investing and managing under such assumptions drives managers to develop plans for learning what needs to be known, a much more effective way to confront disruptive technologies successfully.

Or to repeat one of my other favorite quotes: “Design like you’re right, listen like you’re wrong.” Usability testing gives us a proven process to understand what we got wrong so we can get more of it right. That makes it a methodology we should all invest in more.

-

Who knows, maybe I’ll turn it into a longer, very practical series if there’s interest. ↩

Why it’s more difficult to prioritize features than problems

Daniel Zacarias’s Moving from Solutions to Problems is a must-read for all product managers, and anyone who’s involved in product prioritization. Daniel’s main thesis is that prioritizing problems results in much better products than prioritizing features—and I wholeheartedly agree with him. He addresses many issues with focusing on features, but the one that really resonated with me is that it’s much harder to prioritize features:

Products and features are versions of a solution to a problem. What this means is that by thinking in terms of the former, the problem they’re solving gets more difficult to grasp. Either because it’s a non obvious problem, or the product/feature are poor solutions for it.

In practical terms, this makes it much harder to prioritize a list of features than a list of problems. There are added layers of indirection that make us evaluate priorities in a different way. It gets difficult to determine the intent and expected impact from a feature. On the other hand, a problem (“low number of transactions”) can more easily lead to an objective (“increasing number of transactions per customer per month by 30%”).

Quote: Chloe Green on the ROI of user experience

Numerous studies have found that every dollar spent on UX brings in between $2 and $100 dollars in return. Forrester revealed that ‘implementing a focus on customers’ experience increases their willingness to pay by 14.4 %, reduces their reluctance to switch brands by 15.8 %, and boosts their likelihood to recommend your product by 16.6 %’.

–Chloe Green, The business of user experience: how good UX directly impacts on company performance.

The benefits of prioritizing customer retention over revenues

Horace Dediu has a characteristically astute analysis of Apple’s business model in Priorities in a time of plenty. The part I’m particularly interested in is where he discusses how Apple prioritizes their product roadmap:

Conventionally, product development is filtered through a sieve of metrics, market sizing and impact on top/bottom income lines. These “financial” measures of success are considered prudent and optimized for return on equity (also known as the maximization of shareholder returns).

But this can be a toxic formula. The financial optimization algorithm always prioritizes the known over the unknown since the known can be measured and is assigned a quantum of value while the unknown is “discounted” with a steep hurdle rate, and assigned a near zero net present value. Thus the financial algorithm leads to promoting efficiency at the expense of creation. Efficiency may be the right priority when times are difficult and resources are scarce but creativity is the right priority in a time of plenty. And abundance is what being big is all about.

The difficulty is that creativity is hard to quantify, and therefore hard to measure, and therefore hard to prioritize—particularly in large enterprises. Horace speculates that “the creation and preservation of customers” is Apple’s primary focus (above revenues), which changes the way they prioritize:

Seen this way each centralized resource allocation question can be assumed to be prefaced with “In order to create/preserve customers should we…?”

This leads to answers quite different from questions that start with “In order to sell/profit more should we…?”

Much to digest here, particularly around the role of managers to identify the right balance for prioritization, and the right metrics to measure if your primary goal is, in fact, “the creation and preservation of customers”.

The rise of inclusive design

Cliff Kuang wrote an excellent article on Microsoft’s push for more inclusive design. From Microsoft’s Radical Bet On A New Type Of Design Thinking:

Dubbed inclusive design, it begins with studying overlooked communities, ranging from dyslexics to the deaf. By learning about how they adapt to their world, the hope is that you can actually build better new products for everyone else.

What’s more, by finding more analogues between tribes of people outside the mainstream and situations that we’ve all found ourselves in, you can come up with all kinds of new products. The big idea is that in order to build machines that adapt to humans better, there needs to be a more robust process for watching how humans adapt to each other, and to their world. “The point isn’t to solve for a problem,” such as typing when you’re blind, said Holmes. “We’re flipping it.” They are finding the expertise and ingenuity that arises naturally, when people are forced to live a life differently from most.

This is similar to the points I tried to make in Beyoncé, Coldplay, and the myth of the “average” user. The advantages of having more diversity in our design and development processes go far beyond the moral rightness of it. We end up with better products that serve a much wider cross-section of a population.

Quote: Tomer Sharon on the importance of understanding a problem

The question “How do people currently solve a problem?” is critical, because deeply understanding a problem can go a long way toward solving it with a product, feature, or service. Falling in love with a problem happens through observing it happen in a relevant context, where the problem is occurring to people in your target audience.

—Tomer Sharon, Validating Product Ideas