Janna Bastow wrote a great post on product management for maturing products. From Growing up Lean: Lean Strategies for Maturing Products, here’s a recommendation for how to avoid becoming a “Feature Factory”:

Break the backlog up into two parts: The Product Backlog and the Development Backlog. […]

Product Backlog: A list of all of the things you could do. You’ll never complete everything on this list, and it’ll always be in a constant state of flux. It’ll include customer requests, suggestions from your team, through to insights from your experiments and prototypes. It should be accessible by your team, to both contribute and follow along on progress – your team should be helping to build and flesh out the ideas in your backlog. This is your space to prototype and spec out ideas, map them to your objectives, and track their progress until ready for production.

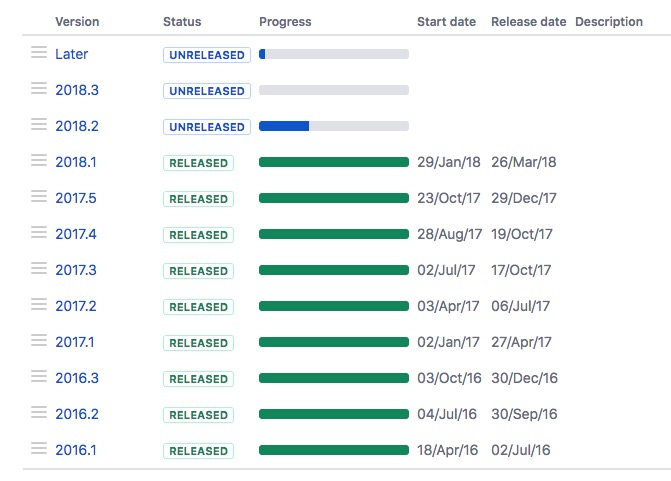

This is similar to how we do things at Postmark. Here is our Releases board in JIRA:

You’ll see that we have our short-term planning (the Development Backlog), that currently only covers 2018.2 and 2018.3 (roughly 6 weeks each). And then we have the mysterious Later release… that’s the Product Backlog. It’s that list of all the things we could do. When we do short-term planning we pull from that list, as well as other areas (most notably, our “Idea Zone” in Basecamp, which I should also write about at some point).

I’ve written about maturing products before as well. I’m happy to see that Jenna and I bring up similar points. Here’s a quote from my post Product Management for well-established products, which echoes some of her thoughts:

With an established product, it’s way too easy to get off track (Evernote, anyone…?). So what I argue for is a flexible quarterly roadmap of prioritized themes. You don’t write down dates next to a long list of features. You don’t make hard commitments for releases that might never happen.

Instead, you put together a list of themes you’d like to work on, in order of priority, based on how closely they align with your objectives and key results for the quarter.