Even though more and more companies are getting comfortable with remote work, the field of product management still seems to push back against this trend quite forcefully. There is a general sense that product managers can’t do the things they need to do unless they are physically located with their teams. This has some ironic consequences, such as that Slack — a company that builds a tool “where work happens” — doesn’t hire remote employees.

I confess that at first I was skeptical as well. But as we started to work together and make progress at Postmark, my skepticism fell away. I do believe it’s harder to make the product management role work remotely than some other roles like customer success or development. But it is possible, and I believe that companies need to start being more open to hiring remote product managers.

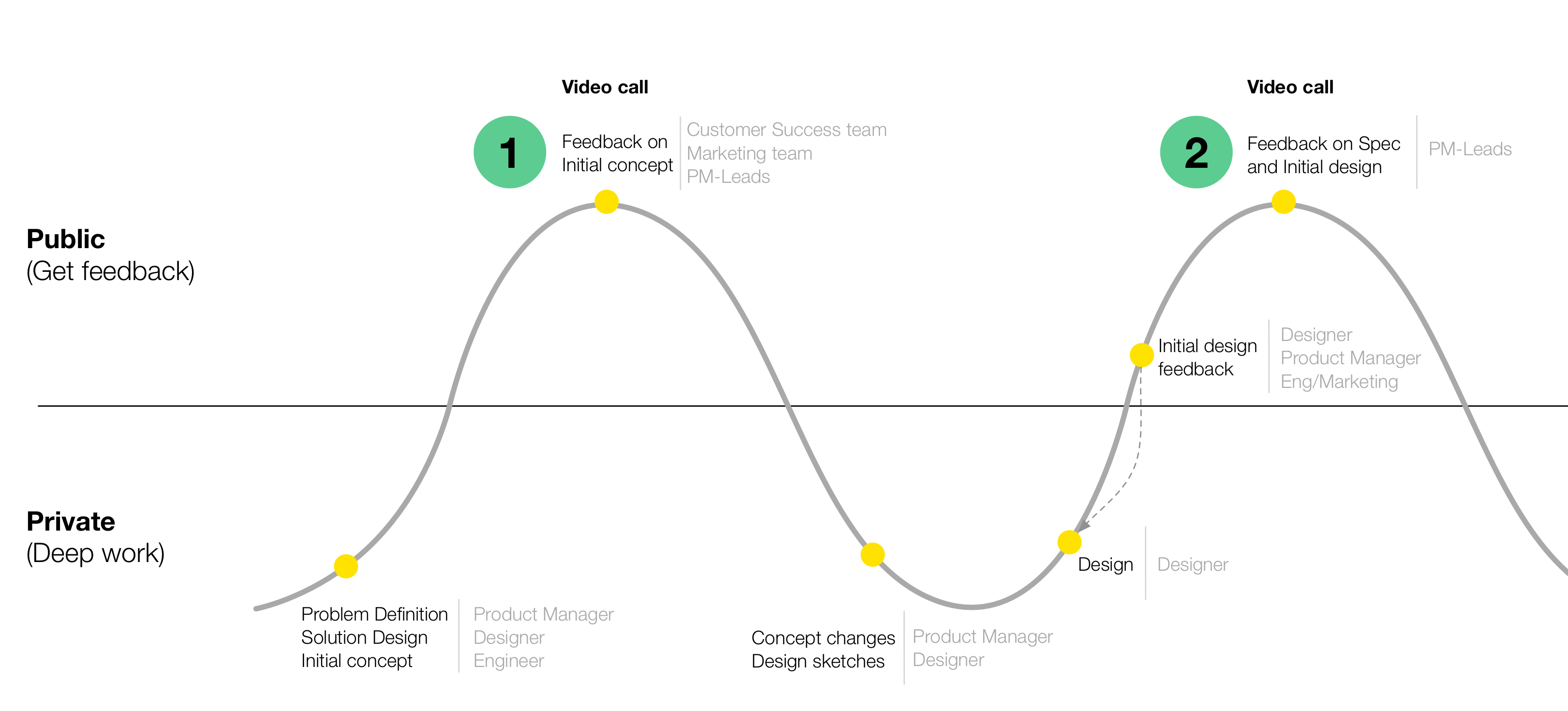

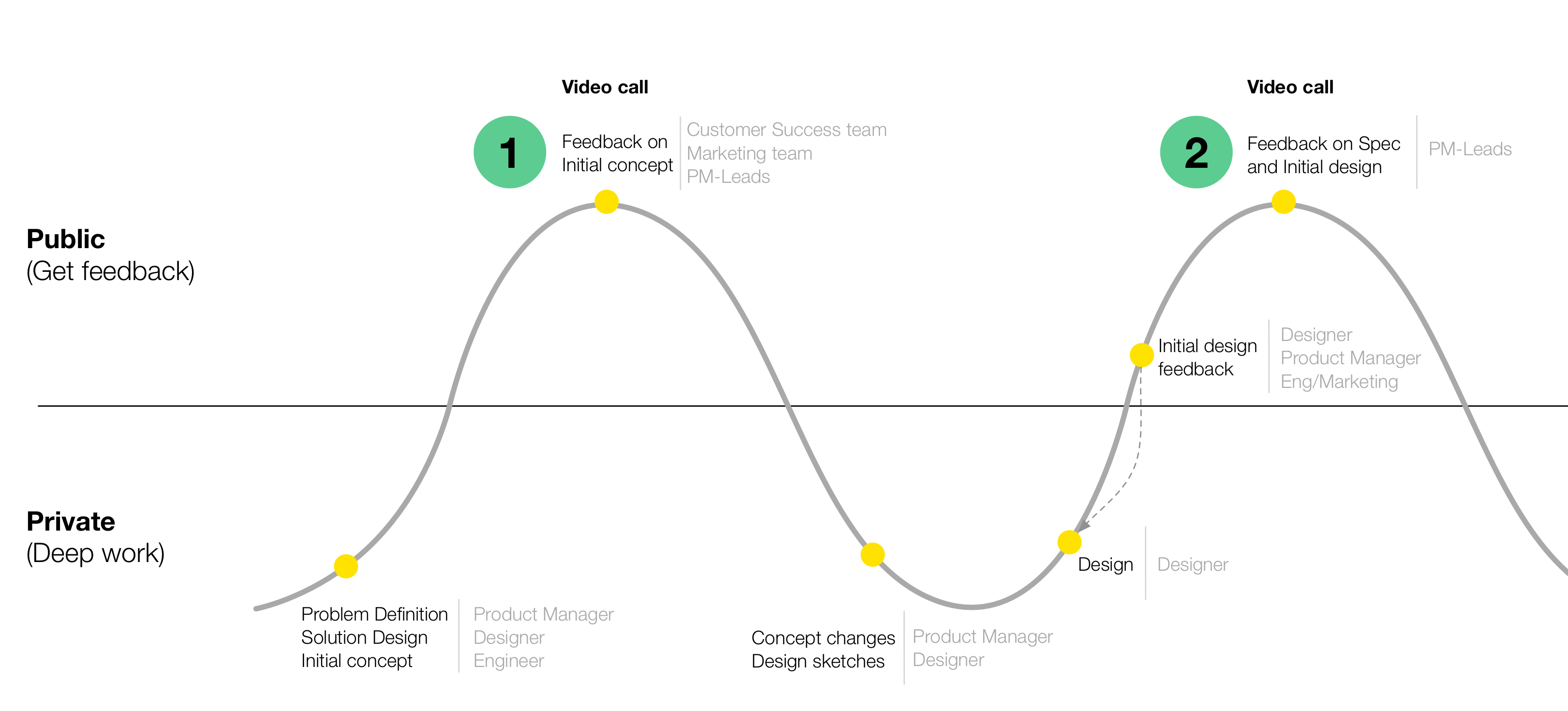

We often hear about the drawbacks of remote work, but it’s important to remember that there are certain things that remote work is naturally better suited for than on-premise work. Most importantly, remote work makes it much easier to develop and instill a rhythm of collaboration and focused time for a team. This rhythm will be different for every team, but I like to think of it as a wave. Here’s one example of what a cycle of private and public work could look like in a team:

Because it’s easier to shut down distractions as a remote worker, the deep work part of that cycle can be immensely efficient and dramatically increase both the speed and quality of work that gets done.

But of course, we can’t ignore the parts of remote work that are challenging and need to be figured out. So in this post I want to share a few lessons I’ve learned over the past 2 years that have helped me to overcome some of the more severe challenges to being an effective remote product manager.

In-person time is still important (but maybe not for the reason we think)

I joined Wildbit at the right time: one week before our yearly in-person company retreat. That gave me an opportunity to meet everyone in person, work together, and most importantly, have meals together. Once you’ve eaten a meal with someone, they’re not an anonymous “colleague” any more. Which means that when conflict arises (and of course it will), you’re way more likely to work through it kindly and respectfully. It’s very difficult to be mad at someone you’ve broken bread with.

The point is that in-person time is extremely important for remote teams. But you don’t need it every day, and the reason you need it is not to get more work done. The reason you need it is to sustain the human relationships that will enable you to get more work done.

When I spend time with our team in person, yes we spend quite a bit of time working together in meetings. But the biggest value for me is the lunches, the coffee chats, and the after-work catch-ups. That’s where we begin to see each other as whole people, and it’s at the core of our ability to work together and grow together.

This is certainly true for the whole team, but it’s especially true as a product manager, where your ability to do your job lives and dies with your ability to have good relationships with the team.

Love your tools (and be prepared to do a bit more of the heavy lifting)

One of our principles at Wildbit is that we optimize for asynchronous communication. We don’t hate meetings. We just value focused work extremely highly, so whenever we can we try to protect that work by giving each person the opportunity to work on something when it’s best for their schedule.

To make this work, you need tools. And those tools have to be light-weight and not a pain to use. Sure, we use Slack (although we’re trying to wean ourselves off it), but most of our collaboration work happens in Dropbox Paper and Basecamp. Those tools are designed for the type of collaboration and asynchronous communication that feels good. It can’t be overstated how important it is for remote teams to love their collaboration tools. If everyone hates the tools, the work will find a way to not get done. You’ll end up blaming “remote culture” and hire an onsite product manager, when the problem lies with crappy tools instead.

The catch is that these tools are just like comments on the internet: if you want them to be useful, you need to be prepared to spend quite a bit of time managing the process and the flow of information. As product manager a big part of my role has become making sure the right people know about things, and the wrong people don’t get distracted by things they don’t need to be involved in. This needs time and care, and doesn’t just happen automatically. The good news is this will still take way less time than “back-to-back meetings” every day…

Make prioritization and planning a team effort (and embrace the benefits of that)

Prioritization and planning of work is difficult under the most ideal circumstances. When you’re working on a remote team, the challenges are even bigger. This is where a combination of the right tools and some deliberate time management can make all the difference. The thing is, we know we do better work when all of our team’s perspectives are taken into consideration — not just in terms of the details of a project, but also what we should work on.

As product manager my role in the prioritization and project planning process is way more traffic controller than it is decider. We use our asynchronous tools to discuss ideas, post and gather feedback on initial drafts of plans, and occasionally even make radical changes to a plan as we learn more from customers and everyone on the team. My one goal is to keep the conversation going. It can be a little chaotic at the start, but I always feel like we end up in a better place than if we used a more traditional prioritization process.

Being a remote product manager is not without its challenges. It can be difficult to get the whole team aligned around a common vision, and you’re not always going to be able to get your questions answered right at the moment you want it. But if you can find a way to focus on and nurture the benefits that are unique to remote work, the challenges tend do get pushed to the background.

To put it another way, I understand why people think that product management isn’t a role that can be done remotely. There’s a lot of team communication involved, and of course that can be challenging over electronic channels. But with a slight shift in the lens you view product management through, those challenges fade away as the benefits of deliberate focused work and carefully considered collaboration come to fruition. I’ll say this: it’s totally worth it.