I hate Microsoft Word. I want Microsoft Word to die. I hate Microsoft Word with a burning, fiery passion. I hate Microsoft Word the way Winston Smith hated Big Brother.

— Charlie Stross

There is a growing uprising against word processors and WYSIWYG editors of late. This is partly because of how bad most of those products are, and partly because other alternatives — particularly plain text — have become so intriguing. In fact, please allow me a moment to declare my undying love for plain text.

I love that with plain text the focus is on the words, not the formatting. I love that it’s portable and can be used anywhere and everywhere, in any piece of software that edits or displays words. I love how easy it is to create beautifully formatted documents when needed. Most of all, I love how fast it is. I simply work more efficiently since switching to plain text.

And yet I haven’t been able to convince many people to join me in uninstalling Microsoft Word and moving most (if not all) of their writing to plain text. You wouldn’t believe how hard it is to find people at a party who are willing to listen to me rant about word processors. So, you know. To the internet!

This is a short post about the tools I use to do the vast majority of my writing (business as well as personal). I hope that it will convince at least some of you to take the plunge with me.

To move your note-taking and writing to plain text you need three things:

- A format to write in

- A place to write in

- A central place to store it all

With those three things in place you’ll be all set to free yourself from the shackles of word processors and WYSIWYG editors. If you want more efficiency and clarity in your writing, this is the way to do it1.

A format to write in

I cannot sing the praises of Markdown enough. Markdown is an easy-to-learn, inconspicuous syntax that lets you focus on what you’re writing without getting bogged down in what it’s going to look like once you’re done. At the same time, it’s a powerful system for formatting documents automatically when you need to print them out, or send something to a colleague or client. The syntax remains easily readable without getting in the way of your words.

I write pretty much everything in Markdown now, and as more and more applications start to support it natively, I only see its popularity growing. The latest email app to take the Mac world by storm, Airmail, has native Markdown support. So does MarsEdit, the software I use to write and publish to this site. The PHP Markdown WordPress plugin further allows any WordPress site to publish with Markdown.

Trust me, it’s really easy to learn. Here’s another Markdown syntax guide to get you going.

A place to write in

Once you’ve settle on the Markdown format, you’re ready for the most difficult stage of the switch: figuring out which of the hundreds of great applications to write and edit plain text files works best for you. On the Mac I’ve tried iA Writer and Byword, but I now spend most of my time in Brett Terpstra’s nvALT. It is a fork of the original Notational Velocity text editor that adds some really great features. What makes it great? Nothing beats nvALT when it comes to speed and efficiency:

- Modeless operation in which searching for notes and creating new notes happen in the same part of the interface. It’s highly efficient and there’s zero lag.

- Powerful keyboard shortcuts for mouseless operation, which further speeds up your writing.

- Native Markdown support, of course.

Even though nvALT has preview functionality built in, I prefer Marked 2 to view formatted text files. Yet another Brett Terpstra project, it’s a powerful previewer for Markdown files, and it works with any text editor. So even if you use something other than nvALT, or open a text file in another app, you can still use Marked. You can add custom CSS and export to a variety of file formats. So when you’re ready to move from words to formatting, this is the app to do it in.

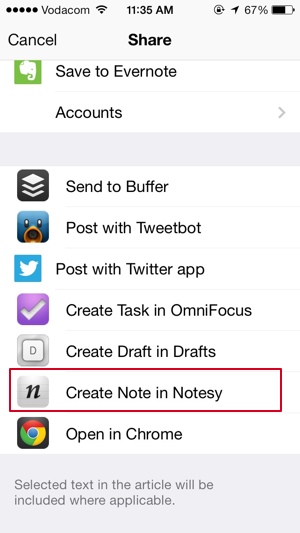

On iOS I’ve gone through tons of text editor apps, but I currently use Notesy, and I’m really happy with it. It’s incredibly fast, which is, as I keep mentioning, one of the main reasons to switch to plain text. There are a few additional things about Notesy that make it one of the apps I use most on my iOS devices:

- You can use it to quickly jot down some thoughts you don’t want to forget, and the file will be waiting for you on nvALT when you get back to your desk. So you can just keep going where you left off.

- It has a URL structure and good support from other apps you may already be using. For example, if you read something in Instapaper that you want to reference in a blog post or an email, you can easily create a note with the selected text.

If you need a more comprehensive overview of iOS text editors, check out this extensive comparison (by — who else — Brett Terpstra).

A central place to store it all.

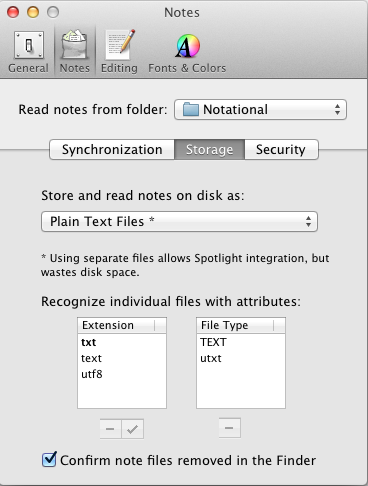

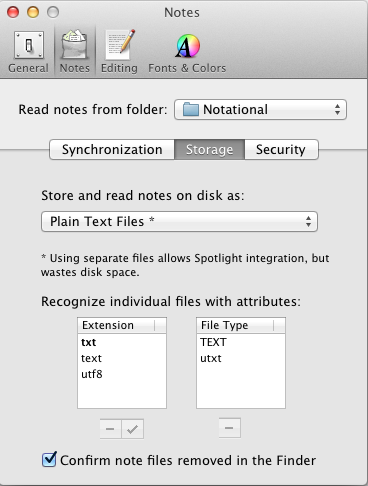

The last thing to figure out is how to make it all work together so your files are always synced and always available for use on any device. Of course, this is where Dropbox comes in. You’ll need to make a couple of simple settings changes in nvALT to accomplish this. In the Notes preference pane, do the following:

- Change the “Read notes from folder” destination to a folder in Dropbox.

- Change the “Store and read notes on disk as:” setting to Plain Text Files

And just like that, you’re all set. Now you can access your text files from any computer that has internet access and an application that can read text files. Notesy on iOS works directly off Dropbox, so you just have to point it to the folder you set up for your plain text files in nvALT.

“But wait,” I hear you say, “what about folders and things?” Well, that’s what’s so great about using nvALT and Notesy. Everything is search-based. I’ve never had a problem finding a file/note I’m looking for. And since these applications are built for speed, even on a vast amount of text files, it’s much faster than trolling through folders looking for the right file. Getting out of the folders mindset is a bit uncomfortable at first, but it really does start to feel natural after a while.

If you really struggle with the idea, nvALT does support tagging (similar to Gmail’s tags), so you can use that as a crutch for a while. But a better option is to come up with a file naming system, and stick with it. See, for example, Michael Schechter’s excellent overview of the system he uses.

“But wait,” I hear you say again (you’re nothing if not persistent), “what about collaborating on documents?” Don’t worry, there’s an app for that. Once you’re at a point where you need to get feedback or collaborate on a document, you can just import your text file into the brilliant new service Editorially, and keep going from there. It supports Markdown (of course it does), version control, tracked changes, and comments. No sweat.

I won’t deny that there are still some circumstances where word processors are useful. I’m writing a book at the moment, and I’m using Pages for that (mainly because Editorially didn’t exist when I started writing it). But for the majority of everyday writing — meeting notes, emails, business documents — there is simply nothing better than plain text. Go ahead. Get rid of Word. You can do it.