I’m a long-time Pinboard fan, and from the moment I became a paid user I couldn’t shake the feeling that it is one of the most underrated services out there. It’s basically the center of my personal internet. I have years of articles tagged and cached, and available immediately whenever I need to remember something. For me, it represents the best of what technology has to offer as an “external brain”1.

But it’s even more powerful than that. I recently started wondering if Pinboard could become more central in my blogging workflow as well. My flow when I find an article I want to write about used to be two steps: (1) save to Pinboard, and then (2) start a new text file (with an excerpt from the article) and start writing.

Since I don’t always have time to write immediately after I read something, the disjointedness of these two steps means that I forget to post articles sometimes — or that I can’t remember which part I want to write about. So I needed a way to save Pinboard links for later, in a way that lets me pick up writing whenever I have time.

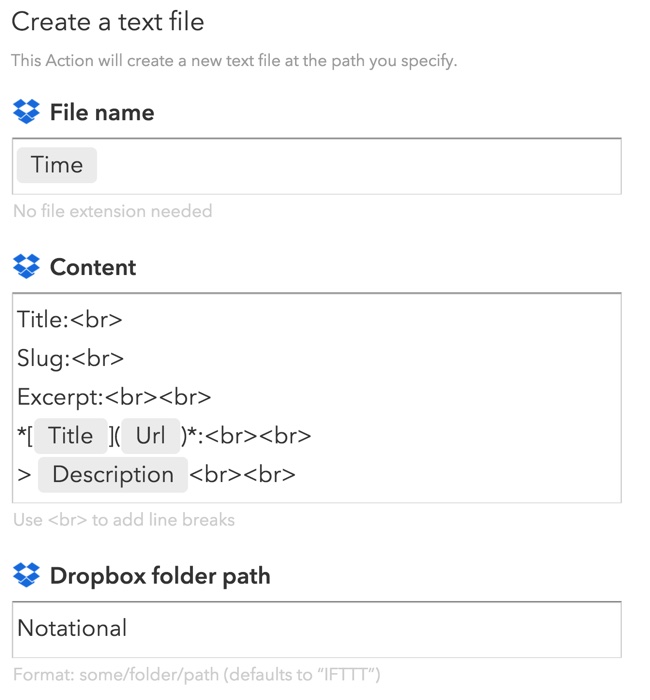

The solution I came up with isn’t rocket science, but it has made such a big difference to the way I write that I wanted to share it here. The key is a simple IFTTT recipe that takes any new link I save to Pinboard and creates a Markdown-formatted text file that I can use to start writing whenever I want to.

Here is a link to the IFTTT recipe: Post any new Pinboard link to a new text file in Dropbox.

And this is what it does:

I always put a pull quote in the “Description” field when I save a Pinboard link, so the recipe creates a text note with a Markdown-formatted URL, the pull quote, and space for me to add a title, slug, and excerpt once I’m ready to post to the site. Putting the note in a Dropbox folder means I can continue typing and editing on any device — I use Editorial on iOS and nvALT on Mac.

As for posting… I still haven’t found a mobile blogging platform that works for me, so even though I write many posts on my iPhone or iPad, I still post exclusively from MarsEdit. So I also went one step further and made a Keyboard Maestro macro (download here) that transfers the text from nvALT to MarsEdit as soon as I’m ready to post.

You know, the internet is pretty cool sometimes.