I want to tell you a quick story about running. And I know it’s a little weird to make everyday life stories about product design but I can’t help myself, so I’m going to do that at the end. Let’s be cool about it, ok?

So.

I hate running. I’ve always hated running. A couple of weeks ago my friend Jason came over for a visit and started asking me about it. He wouldn’t let up. Bastard kept pressing. “Why do you hate running so much?” Over and over and over. Eventually we narrowed it down to breathing. I’ve always felt uncomfortably out of breath when I run. This is when my wife joined the party, and feeding off each other, they kept at it.

What felt like hours later, through their incessant questioning, we figured out that I’ve been breathing ridiculously wrong during my runs for two decades. For reasons that I am unable to explain, I’ve always timed my in-and-out breathing with every third step. Not second. Not fourth. THIRD. The result is that I’ve basically been hyperventilating through my runs for the better part of 20 years.

Anyway, they coached me for about five minutes on how to breathe. Turns out — and this is going to blow your mind — your body knows when it has to breathe. All you have to do is stop trying to force some kind of rhythm. Just focus on getting as much oxygen into your lungs as you possibly can, and then letting it out slowly. Your body will find its own rhythm.

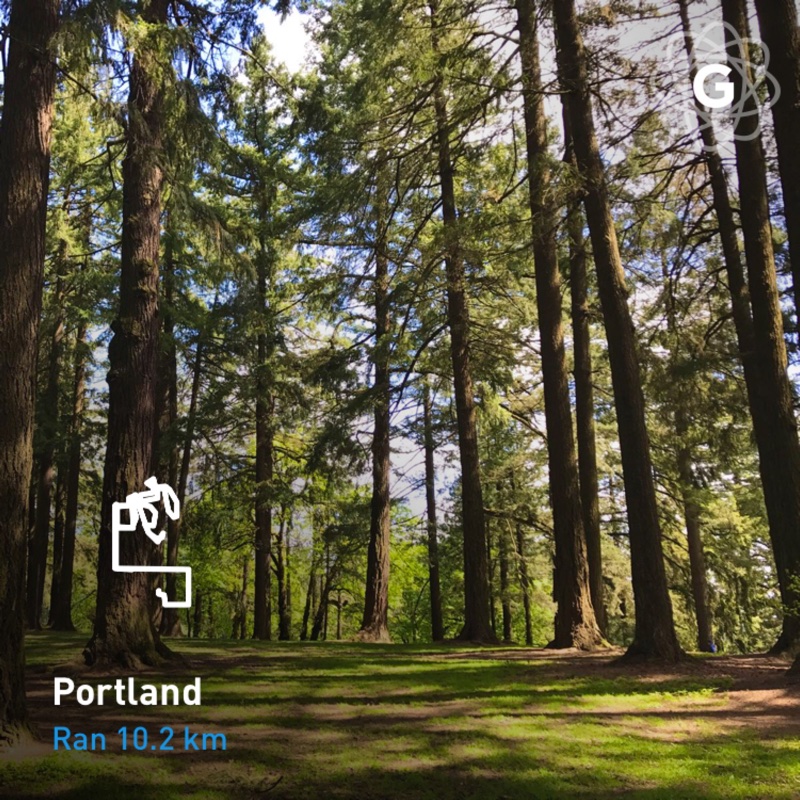

The next day I tried out this revolutionary breathing mechanism. Not only was it enjoyable, I ran faster and further than usual. Last weekend, not even two weeks after they accosted me, I went for a 10k run. It was my fastest 10k ever, and more importantly, I enjoyed it.

I keep switching back and forth between being really pissed that I’ve been doing it wrong for so long, and ecstatic that I’ve been able to figure out the issue. I’m still blown away that a change in breathing can have such an immediate and enormous impact. Mostly, I’m thankful for my friend and my wife, who persisted way past the point of annoyance, and gave me a new lease on running (and, not to be dramatic, but life too).

Here’s where we get to the product design bit. This experience taught me another lesson, something that’s already deeply ingrained but I still forget it sometimes:

You cannot come up with a good solution before you understand the problem completely.

I tried that shortcut with the running thing. I switched up the cadence, or tried to just “break through the wall”. It wasn’t until someone pushed me to get to the cause of it all that we were able to find the right solution. So I resolved to be just a little more annoying at work. All it really comes down to is asking Why? a few more times than I think I should. I know that the answers will help us understand what we’re trying to accomplish, and building a better product for our customers.