The article Air France Flight 447: “Damn it, we’re going to crash” is long and fascinating. But most of all, it’s frightening. It paints a vivid picture of what happened the night of June 1st 2009, when Air France Flight 447 from Rio de Janeiro to Paris went missing. The plane was eventually found days later – all 228 passengers and crew died in the crash.

For me, the biggest take-away from the article is that sometimes bad design can cost lives. Much of the article is about the design flaws in Airbus planes that resulted in multiple – and eventually fatal – human errors by the pilots. The details are important so you should definitely read the whole article, but two main design issues are discussed.

First, there is a lack of information given to pilots:

In the next 40 seconds AF447 fell 3,000 feet, losing more and more speed as the angle of attack increased to 40 degrees. The wings were now like bulldozer blades against the sky. Bonin failed to grasp this fact, and though angle of attack readings are sent to onboard computers, there are no displays in modern jets to convey this critical information to the crews. One of the provisional recommendations of the BEA inquiry has been to challenge this absence.

Second, there is a lack of visual feedback on the particular kind of steering that’s used on all Airbus planes. Because of the way the so-called “fly-by-wire” steering method is implemented on the Airbus, it’s very difficult for pilots to see what their colleagues are doing, and therefore almost impossible to spot human error:

The American manufacturer [Boeing] was concerned about [the Airbus] side sticks’ lack of visual and physical feedback. Indeed, it is hard to believe AF447 would have fallen from the sky if it had been a Boeing. Had a traditional yoke been installed on Flight AF447, Robert would surely have realised that his junior colleague had the lever pulled back and mostly kept it there. When Dubois returned to the cockpit he would have seen that Bonin was pulling up the nose.

As I read through this article I was immediately reminded of Nielsen’s first usability heuristic:

Visibility of system status

The system should always keep users informed about what is going on, through appropriate feedback within reasonable time.

Both of the main issues that resulted in the crash of Flight AF447 could have been avoided by following the simple guidelines of system status visibility. It’s what makes this already horrifying event even worse.

As web designers we are extremely lucky – our design mistakes don’t endanger lives. But even though we don’t make daily life-or-death decisions in our profession, we should still pay extra attention to this first, and arguably most important, rule of UI design: always make sure users know where they are, and that they have the information they need to make their next decision. This is one of those simple design rules that seems obvious when it’s followed, but results in major abandonment when it’s broken.

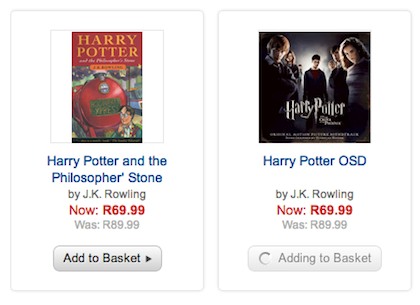

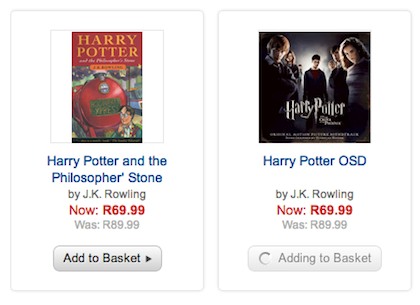

When a user gives an input we have to acknowledge receipt of that input. This input is usually in the form of a click or a touch. It’s the user’s way of starting a conversation, so don’t be rude – talk back. These buttons below, designed by Alex Maughan for kalahari.com, is a good example of appropriate feedback:

As soon as the user clicks the “Add to basket” button, the animated spinner and text give an indication that something is happening. Or consider this idea for a new kind of signup flow outlined on the 37signals blog:

You could preview the workflow steps that come after the signup so it’s clear how much of a gap there is between signing up and getting value out of the product.

This approach gives users comfort, because they know what’s going to happen next. They have all the information they need, so there’s no need to panic and abandon the flow. (You can click through to the original post for a sketch of this idea)

This principle isn’t new or complicated. But reading about the Air France tragedy reminded me again that we sometimes skip over the basics to implement the fancy. So here’s an idea: pick your favorite “get the basics right” sports cliché and put it on the wall so you can see it whenever you’re designing (you know, like catches win matches or something). Or just get straight to the point and write, “Appropriate feedback makes for happy users”.