Last week I used a product development theory called the Kano Model to explain why it’s wrong to be disappointed with the iPhone 5. I wrote the article just before the launch event, and lo and behold, it didn’t take long for the Internet to start yawning:

Um, it’s a little bit longer. Really Apple? You spent months in court fighting Samsung and portraying yourself as the world’s only truly innovative company and this is the best you can do? A phone that looks like what would happen if phones were capable of inbreeding?

Today I’d like to explore the fallacy of this kind of disappointment further using a mathematical theory I alluded to in my previous article, Maxima and Minima:

In mathematics, the maximum and minimum of a function are the largest and smallest value that the function takes at a point either within a given neighborhood (local or relative extremum) or on the function domain in its entirety (global or absolute extremum)

More specifically, I want to discuss the idea of the local maximum within the context of product development, and how that relates to innovation. For the purposes of product development, I liken the mathematical concept of neighborhood to product. For example, the iPhone (as a product) will hit a local maximum when the current design cannot be improved any more. This isn’t necessarily the best product you can make in the entire industry, but it is the best iteration of the current product1.

(Image source: 52weeksofux)

To explore this further, we also have to differentiate between the concepts of iteration and variation. In product development, variation is a way to explore a bunch of alternative product solutions. In contrast, iteration solidifies the product idea that gets chosen. To quote Jon Kolko: “Where an iteration moves an idea forward (or backwards), a variation moves an idea left or right.” Or, to put it into the language of maxima and minima, variation surveys the landscape to help companies choose the right neighborhood (product) to move into. Iteration then helps them to find the local maximum in their chosen neighborhood.

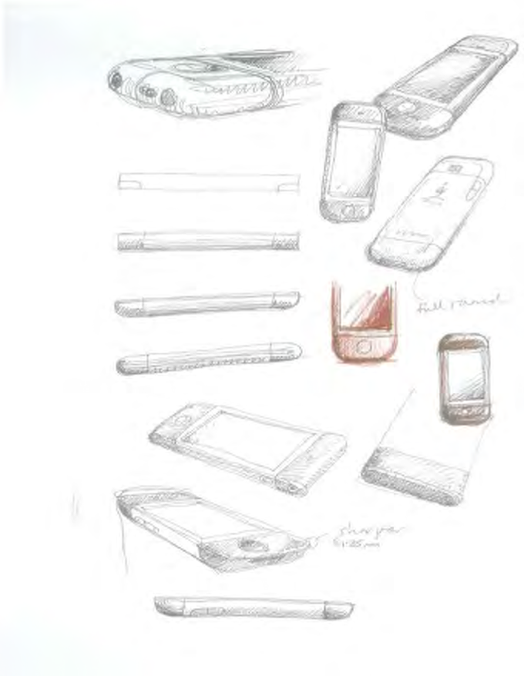

Now, let’s look at the iPhone. Because of the Samsung trial we know that Apple did a great deal of variation work before they chose their neighborhood. See, for example, this sketch of different possible designs from a slide show on AllThingsD:

(Image source: AllThingsD)

If you dig deeper into the slide show you’ll see many variations they considered before settling on the basic design for the original iPhone.

It’s not just the hardware though, of course. There’s also iOS. As far as I’m aware there aren’t any early sketches for iOS publicly available, but I’m willing to bet a lot of money that they didn’t just sketch one thing and then designed it that way. It’s pretty safe to assume that the variation process on iOS was every bit as rigorous as for the iPhone hardware.

Once they’ve done a bunch of variation work on the hardware and software for the iPhone, Apple chose their neighborhood and started iterating. There were some major improvement jumps along the way (like iOS2, and iPhone 4), but it’s all still in the same neighborhood.

So let’s get to the crux of the matter. From an engineering perspective, variation is expensive, iteration is cheap. Especially if a product is already out there. Apple is able to give away the iPhone 4 for free because they have been iterating on the hardware for so long that they can manufacture the phones very cheaply. If the iPhone 5 was a drastically different phone (I’m talking about a completely different neighborhood), everything would have started from zero.

From a business perspective, why would Apple choose to make a very expensive move to a different neighborhood, when they know that they haven’t hit the local maximum on the current phone yet? Apple is iterating because they understand this concept, and because they know that the only thing that matters is if customers like it. As John Gruber said:

The collective yawn from the tech press was louder this year; the enthusiasm from consumers is stronger.

What does it mean for startups?

There are some important lessons for startups in the story of the iPhone evolution.

First, spend as much time and money as you can afford on variation upfront, because if you move into the wrong neighborhood, it’s really hard to change that later on. Some companies have done it successfully, like when Path completely redesigned their product from the ground up. Other companies are finding it really hard to move, as evidenced by the almost universal disdain for the new Twitter app for iPad2. And the jury is still out on whether Microsoft’s very expensive foray into the tablet OS world will be a success or not.

Second, don’t move to a new neighborhood until you’re absolutely sure that you’ve hit the local maximum right where you live. I’ll say it again – iteration is cheaper than variation. Instead of trying to rethink your product every few months/years, rather spend time to understand how you can make the current variation better. Apple is proof that this strategy pays off.

I have a feeling that Apple isn’t going to move out of their phone neighborhood any time soon. They might send some family members to buy a new house in the TV neighborhood. But when it comes to phones, they’re still on to a good thing, and they’re smart enough not to be tempted by the fake grass on the other side of the “change everything!” fence.