Working with people can be hard. Designing with people can be even harder. Designing with people who are not in the same location can be almost impossible. There’s no perfect solution for working in distributed teams, but if there’s one tool that seems to get our community further than most, it’s Trello. I’ve seen some really great Trello workflow posts over the past few months:

- How we use Trello & Google Docs to make UserVoice better every day

- Coordinating with Cards (Kickstarter)

- How We Make Trello (Fog Creek)

We have a distributed team across Portland, OR and Dallas, TX, and we use a workflow similar to the ones above, but different enough to make me think it might be worth sharing.

As background, we have a team of 5 UX Designers who split their time across 3 main products as well as our internal Pattern Library. Each product has a Design Lead (this role can rotate), and we define the Lead’s responsibilities as follows:

- Understanding and documenting user needs, business goals, and technical constraints before any design work starts.

- Being the single point of contact for any design questions by Product Managers or the rest of the business.

- Making sure Trello is updated with latest priorities, due dates, and artifacts.

- Making tie-breaker design decisions as needed and required if there are design disagreements and we can’t reach consensus.

- Designing interactions and screens, and/or implement those designs in the pattern library, and distribute the workload to other designers as needed and capacity allows.

- Explaining and defending design decisions, even at 8:30am before having a cup of coffee.

Granted, that last requirement is a bit harsh, but we set high standards for ourselves here.

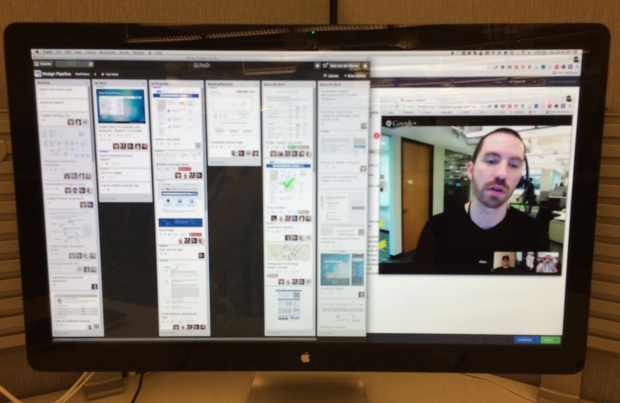

Anyway. Our week starts on Thursday mornings with a Design Pipeline meeting where we go through our upcoming tasks as a team, give each other design feedback, and play with the animations in Google Hangouts. Here is a typical Thursday morning view — Trello on the left, Google Hangouts on the right:

Each Design Lead comes to this meeting with an understanding of their Product Manager’s main priorities so that we can discuss how to divide up the work. As you can see above our Trello board has 6 columns:

- Backlog: Work that’s coming down the road, prioritized every week by the Design Lead after talking to their Product Manager.

- Up Next: What we’re going to work on next once current tasks are complete. We use our Pipeline meeting to pull cards out of the Backlog and into the Up Next column.

- In Progress: In typical Kanban fashion we try to limit work-in-progress, so for a card to be in this column it really has to be in progress. During our Thursday meeting we have an opportunity to give feedback and help each other out on any questions we might have.

- Waiting/Blocked: If something can’t move forward it can’t just sit in In Progress gathering dust — we have to move it into this column. This gives me an opportunity to know where I need to get involved to unblock things if necessary.

- Done (current quarter) and Done (previous quarter): We keep two quarters of completed cards in the history, and archive further back. If everything goes into one big Done column it just becomes really unwieldy.

A couple of other random points:

- We use Trello’s color labels to indicate who’s responsible for each card, since it’s not possible to assign a single point of contact to a Trello card (unless you remove the watchers, which kind of defeats the point of, you know, collaboration software).

- We all dial into Google Hangouts separately from our desks. I find that if you have two rooms and a single dial-in it’s easy to get distracted or for side discussion to start happening. This approach puts everyone on the same playing field, and as an added bonus we can all update Trello together.

During the week we use Trello as a running News Feed of what’s happening on each of our tasks, but sometimes that’s not enough. For ad hoc design feedback during the week we using InVision, a tool I dearly love, and not just because they sent me this nice coaster in the mail (thanks guys!):

InVision is more of an internal scratchpad — a safe place where we can work together as a team and ask each other tough questions about our designs. In contrast, Trello is the paper of record for each of our revisions that we share with anyone who’s interested. It works well for us to separate those spaces out.

The combination of Trello, InVision, and Google Hangouts don’t make up for in-person time (I hope for at least some of us to be in the same space every couple of months), but it sure makes it easier than email and Lync, which is THE BIGGEST PILE OF CRAP SOFTWARE EVER CREATED.

The kicker is that our organization is finally moving to JIRA and Confluence, so we’re currently messing around with Kanban boards in JIRA to replace the Trello bit of this workflow. If we ever figure that out, I’ll write another post about. But for now, this is how we work. I’d love to see how you do it. Write a post, send it to me, and I’ll link to it here.