I’ve been spending lots of time recently thinking about and working with my team on what I can only refer to as “how we should spend our life force.” If that sounds weird, hold on to your hats because I’m going to make it even weirder by (and I apologize in advance) throwing a 2×2 matrix into the mix. So. Come with me in this post as we discuss how our biggest strength as product managers can easily become our biggest weakness, and how we can protect our health and sanity in the midst of all the turmoil in our companies and the world at large.

First, without getting too deep into the metaphysical or get myself in trouble about things I don’t know enough about, I do think it’s import for each of us to make conscious decisions to spend our “life force” on things that make us generally feel fulfilled and bring us closer to the person we want to be. That can take many forms—a bike ride, a fun side project, a bad action show (The Night Desk is so bad good!), an interesting problem at work… those can all be good ways to spend our life force! Being on the internet too long, on the other hand, is rarely that:

This is true at a macro level in our daily lives, but also when we zoom into how we spend our time at work. PMs in particular have this annoying habit where we tend to gravitate towards the wicked problems—a trait that makes us good at what we do, but can also be self-defeating because when we spend too much of our time depleting our life force, burnout eventually finds us.

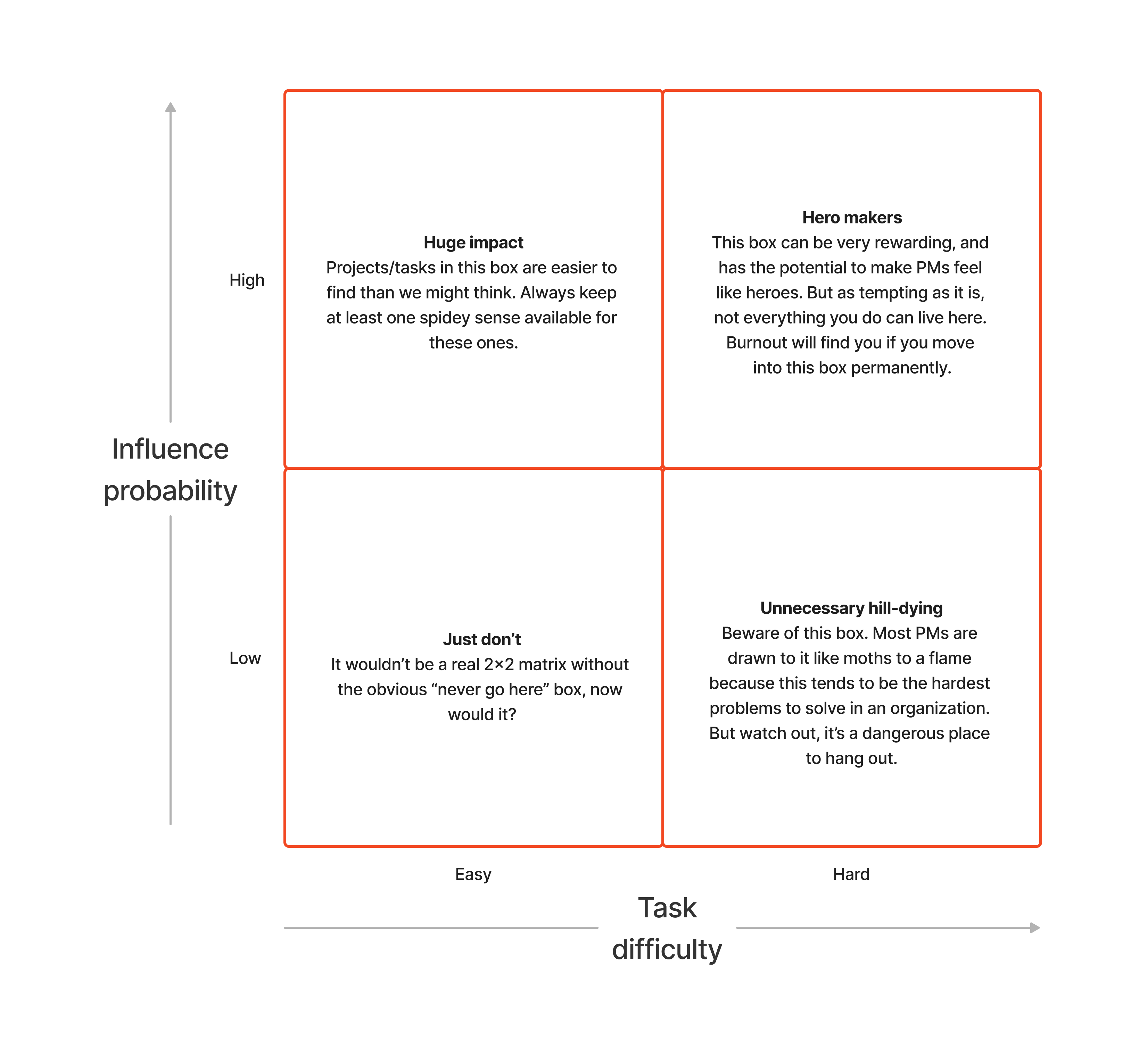

So 2×2 matrix incoming! I think of the way we spend our life force as PMs on two dimensions: the difficulty of the task, and our likelihood of influencing the task’s success.

Some tasks fall in the easy bucket (relatively speaking—don’t @ me!). Think about things like customer interviews, collaborating with designers on a good user experience for a feature, or puttering around in JIRA making comments here and there. But then there are the difficult tasks—solving an organization’s quality problem, fixing development and deployment dependencies, understand team dynamics and creating a safe and open work environment where the whole team feels happy and fulfilled… you get the idea.

We are probably all familiar with that dimension. But the dimension we don’t always take into account is the probability that our work will actually influence the outcome of the task to ensure its success. Maybe the collaboration with the designer has a low probability of success because they report into a different org with different values. Maybe fixing development and deployment dependencies have a high probability of success because you have a really good relationship with engineering leadership and you all are highly motivated to solve the problem.

Which leads me to my main point. It’s in the combination of the ease/effort involved in a task, as well as our known sphere of influence, that we are able to make the best decisions about where to spend our life force. Let’s break out that long-promised matrix now, shall we?

You’ll have to excuse me, I’m not good at naming things. But let’s go through these.

Just don’t

Let’s get this one out of the way first. There are tasks that are easy, that we might be tempted to pick up—especially when we’re already tired and close to burnout—that simply don’t make sense because there really is no winning.

Maybe you are a JIRA wizard, and you think it would be an easy win to redo some of your workflows. But maybe the engineering team has no interest in changing any workflows and they see no benefit in learning a new system. They dig their heals in, and before you know it you’ve spent weeks on an “easy” task that only served to erode trust between you and the engineering team.

Just don’t.

Unnecessary hill-dying

This bucket is really interesting to me because I think a lot of ambitious, smart PMs gravitate towards problems like these. We want to go for the hardest, “wickedest” problems out there, and prove to ourselves and the world that we can solve them. This is such an admirable quality, but not a sustainable way to live your work-life.

Think of our example of solving an organization’s quality problem. This is likely a really hard problem that requires coordination and buy-in across multiple teams, with a lot of resistance and meetings and meetings about meetings and meetings to talk about how bad that one meeting went. With extensive effort and superhuman patience and collaboration skills you might get to a point in 9–12 months where the quality of the organization’s output has seen a marked improvement. At that point it will feel amazing and you’ll be proud—as you should be. But it might also kill your drive, enthusiasm, and ambition and turn you into a relentless cynic.

I think we should all attempt a task like this at least once in our careers. But it is no place to build a home.

Hero makers

Oh, we love these kinds of tasks too, don’t we. Really hard problems with enough social and organizational capital to make a real difference in a reasonable time frame? That’s PM catnip right there! This box is definitely a better use of life force than unnecessary hill-dying, but we have to limit ourselves here too. Because even though the payoff / enjoyment / fulfillment of this work can be huge, so can the cost. This is difficult work that can also become addictive, and if we don’t pace ourselves and limit the number of tasks we take on in this box, burnout will find us here. So choose these carefully, and try to shift more of your life force to…

Huge impact

As we progress in our careers some tasks that used to be difficult become second nature to us. What sometimes happens is that we forget that it wasn’t always easy, so we erroneously start to think that everyone on the team already knows what we know, and we start to undervalue our contributions / knowledge.

Take a moment to think if this is happening to you. Maybe you have gotten really good at JTBD interviews, or facilitating group FigJam sessions, or getting a team to define a customer problem / business outcome effectively, or… What are the things that you can do in your sleep, but only because you’ve spent so much time on those tasks that you have a level of familiarity that others on the team simply don’t have?

Those, my friend, are high impact tasks that take very little energy/life force, and often gives you energy because of how electrifying it can be to be really good at something. You should always be on the lookout for ways to apply those unique skills to problems/opportunities where it can be really impactful. Unfortunately we can’t spend 100% of our time on tasks like these—and frankly, we shouldn’t want that, because then we’ll stop growing. But the number should definitely be more than 0% and probably closer to 20% of our time.

The main point I want to make with this post is that as PMs we generally have a lot of autonomy over how we spend our time, and that can be a blessing and a curse. A blessing because we get to prioritize our impact. A curse because we too often spend our life force on tasks that drain us and lead us towards burnout.

So take a moment to breathe, and think about the amount of time you spend in each of the life force buckets I mentioned here—and where you might need to make changes to avoid the road to exhaustion and burnout. And please, come up with better names for the buckets than I did.