The air of ‘meh’ surrounding Apple’s iPhone event this coming Wednesday is almost palpable. A wave of pre-disappointment is sweeping much of the tech blog world, with proclamations like this one from Andrew Couts:

As bored as I am by the new iPhone’s purported growth spurt, I’m not particularly interested in any of the other realistic features Apple might add to some “dream phone” either. NFC? Yawn. Quad-core processor? Psh. Wireless charging? Whatevs. All these features would be great, I suppose — but they have been done before, and will be done again and again and again by the time the iPhone 6 makes its way into the world around this time next year.

I’ve been wondering why so many people have gone all “Everything’s amazing and nobody’s happy” on Apple with this particular event. And I think the answer lies in an unlikely place: a product development theory called the Kano Model.

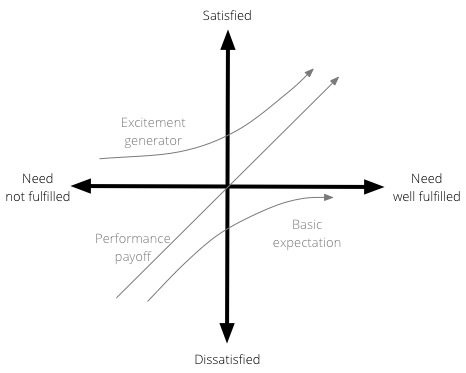

The Kano Model, developed in the 1980s by Professor Noriaki Kano for the Japanese automotive industry, is a helpful method to prioritise product features by plotting them on the following 2-dimensional scale:

- How well a particular user need is being fulfilled by a feature

- What level of satisfaction the feature will give users

The model is generally used to classify features into three groups:

- Excitement generators. Delightful, unexpected features that make a product both useful and usable.

- Performance payoffs. Features that continue to increase satisfaction as improvements are made.

- Basic expectations. Features that users expect as a given — if these aren’t available in a product, you’re in trouble.

Here is a visual representation of the Kano model:

Now, let’s look at the iPhone in this context. When it was first introduced it was all Excitement generators all the way. From the touch screen, to the scrolling, to the tiniest of UI details, the thing was just a joy to use from start to finish. And since no one had seen anything like it before, we thought it was a piece of magic that could do anything:

(Image source: Cyanide & Happiness)

Eventually the novelty wore off and the iPhone’s Excitement generators became Basic expectations since everyone started doing it (oh hi, Samsung!). But there were still plenty of Performance payoff features to work on. Continued UI refinements, 3rd party apps, enterprise support, push notifications… as those features were introduced and improved, we kept liking the device more.

This couldn’t go on forever, though. The natural evolution of most products is that the Excitement generators become harder to find, so you tend to spend more time on the Performance payoffs and Basic expectations1. For example, by the time cut-and-paste came to the iPhone, it was no longer an Excitement generator, but the most basic of expectations. All the features Andrew Couts talks about in the piece I quoted above are Basic expectations as well. John Gruber wrote about this back in May:

iOS is by no means feature-complete. But it’s getting harder to identify the low-hanging fruit — the things you just know Apple has to be working on, not just the stuff you hope they are.

There is nothing wrong with this. It’s a natural evolution of a product, and we should be happy with the incremental progress. But that’s just not good enough for us. We can’t move beyond the amazing 2007 keynote where we first saw the iPhone. That’s where Apple set the bar, and now it’s almost impossible to reach it again. So, even though every year the iPhone and iOS keep getting better and better, we become less and less impressed because we have an unrealistic expectation that everything Apple does has to fit into the Excitement generator category. It’s impossible. No one can do that ad infinitum.

We should stop hoping for an avalanche of Excitement generators in this week’s announcement of the new iPhone. Instead, we should realise that Apple is doing what any company should do with a mature product: focus on ways to increase customer satisfaction steadily with Performance payoff and Basic expectation features, without getting caught up in a wild goose chase to re-invent a product that already re-invented an industry.

-

Also see the Local Maximum theory, which suggests that each design has a limit where it’s as effective as it’s ever going to be. ↩