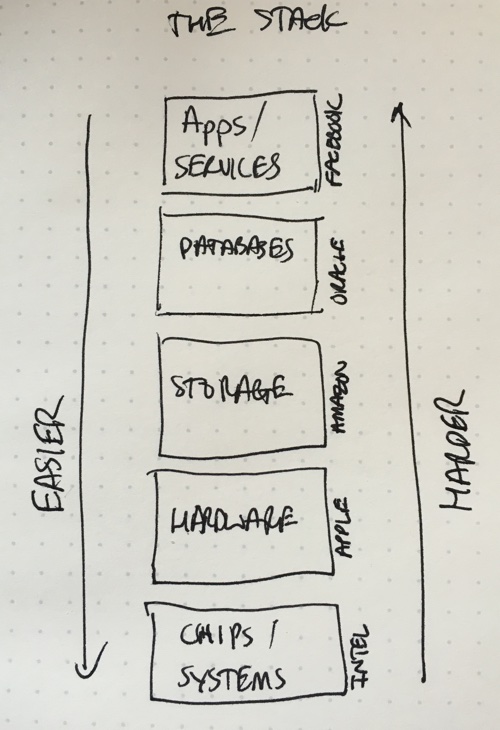

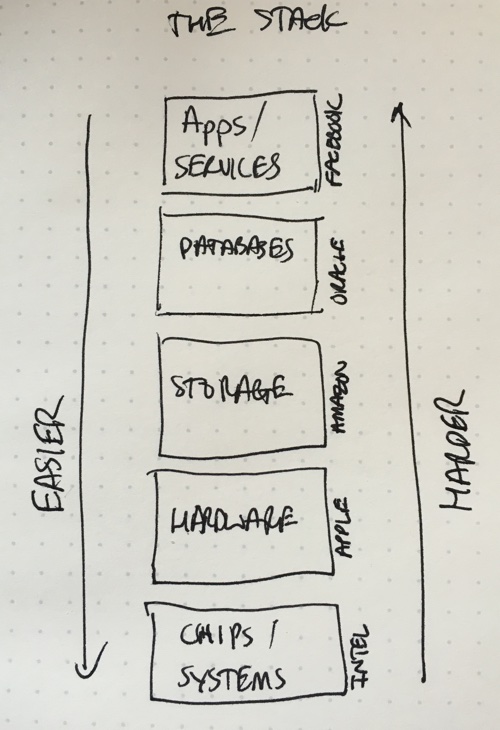

I’ve seen Anshu Sharma’s Why Big Companies Keep Failing: The Stack Fallacy come up in my feeds a bunch of times over the last couple of days. I personally found the writing quite confusing, and had to read it several times to figure out what he was trying to say. I even drew a picture to help me.

If I understand the argument correctly, Anshu is saying that wherever your core business is in the technology stack, it’s easier to expand your market by going down the stack than up. Like so:

This is obviously an oversimplification and leaves a lot of things out, but it was just a way for me to make sense of the article. That said, it’s this part in particular that stood out for me:

The bottleneck for success often is not knowledge of the tools, but lack of understanding of the customer needs. Database engineers know almost nothing about what supply chain software customers want or need. They can hire for that, but it is not a core competency.

The reason for this is that you are yourself a natural customer of the lower layers. Apple knew what it wanted from an ideal future microprocessor. It did not have the skills necessary to build it, but the customer needs were well understood. Technical skills can be bought/acquired, whereas it is very hard to buy a deep understanding of market needs.

In other words, it’s easier for Apple to take on Intel than it is for Apple to take on Facebook. Likewise, it’s easier for Amazon (AWS) to take on hardware manufacturers than it is for them to take on Salesforce. And the reason for this is that most companies understand the customer needs of the components their core business is built out of, but they don’t understand the customer needs of the businesses that other companies build using their components.

Update: This tweet from Peter Matthaei is a much better summary than the one I came up with:

It’s an interesting theory, especially if you consider the logical conclusion that apps and services like Facebook and Salesforce (etc.) are at the top of the stack, and everyone not originally in the software business is going to have a really difficult time competing with them. I’d be curious to hear what others think of this…