I flew up to Joburg this weekend to speak at one of the World IA Day events that were happening in 14 cities around the world. The bulk of the talk was about Customer Journey Maps, and specifically how we used the technique to help us prioritize our roadmap at kalahari.com. In this summary post I want to focus primarily on the topic I started the talk with. It’s about a particular gap I see in current UX work, and how Information Architecture is uniquely positioned to bridge this gap.

In 1955 David Ogilvey wrote a letter about his copywriting habits, and among other things, said the following about campaign work:

I write out a definition of the problem and a statement of the purpose which I wish the campaign to achieve. Then I go no further until the statement and its principles have been accepted by the client.

It seems that ther’s unfortunately plenty of UX work out there that jumps straight into wireframes without first understanding the design problem, as well as the purpose of the solution. Purpose – the reason for which something is done or created – often appears to be missing (*cough* Color.com *cough*). And this is where I believe Information Architecture can come to the rescue.

There are plenty of definitions of IA to choose from, but I like this one in particular by Peter Morville:

I like it because it brings into focus the idea that at its core, Information Architecture is about a unique way of seeing the world. A way that is essential to build successful user experiences.

I love the example Dan Klyn’s uses in Information Architecture is a Way of Seeing. You have to read the whole thing to appreciate it fully, but in short, he tells a story about having to deal with some pretty severe back pain recently. After visiting an MD who only gave him a prescription for Vicodin and some exercises that didn’t help at all, he ended up at a Chiropractor who was able to sort out the problem in just a few days (after taking an X-ray to help diagnose the problem). When asked why the MD didn’t originally take an X-ray to get to the root of the problem, the Chiropractor replied that it wouldn’t have mattered if she did:

Even if the MD had taken an X-Ray, she would not have seen what I saw. Show us each the same image and we see different stuff.

It’s this different way of seeing that makes the IA profession so crucial right now. IAs specialize in looking at a vast amount of information and making sense of it in a way that is credible, consumable, and relevant to users (and the business). Where most of us only see Navigation, they know that part is just the tip of the iceberg. Underneath it lie activities like Information organization, Information relationships, and IA research that all work together to give IAs their unique view of the world.

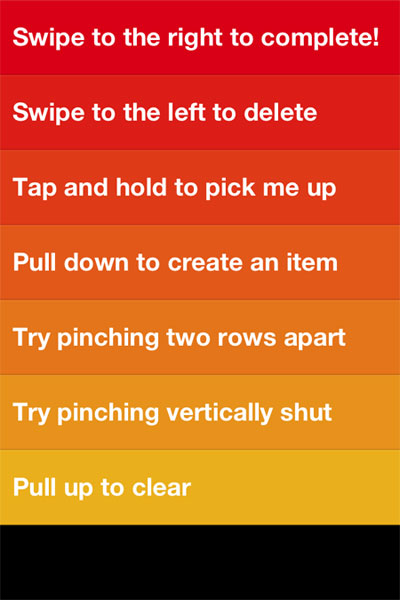

Within this large toolset that IAs have to choose from to do their work, Customer Journey Maps stand out as the one technique that can be most effective to bring purpose back to our UX work. As UX Matters defines it:

Customer journey maps are documents that visually illustrate an individual customer’s needs, the series of interactions that are necessary to fulfill those needs, and the resulting emotional states a customer experiences throughout the process.

These maps are important as a way to find UX purpose because it accomplishes the following goals:

- It provides a common understanding within an organization about customer needs, product strategy, and business goals – i.e., the product’s reason to exist.

- It’s an excellent product prioritization tool.

- It’s a guiding light for design, always bringing the project and the process back to the customer journey and the purpose of the product.

There are many different ways to approach these maps, but I find the Adaptive Path way the most effective. It places a strong focus on user research, and forces you to think about the implications of the journey map, and how it can integrate with and guide the design process.

So, that was my story at the conference. Thanks to everyone who came out! Here are the slides from my talk: