I was encouraged to read these words by Matt Mullenweg in his post Radically Simplified WordPress:

As John Borthwick put beautifully today, “A tablet is an incredible device that you can put in front of babies or 95-year-olds and they know how to use it.” How we democratize publishing on that sort of platform will not and should not work like WordPress’ current dashboard does. It’s not a matter of a responsive stylesheet or incremental UX improvements, it’s re-imagining and radically simplifying what we currently do, thinking outside the box of wp-admin.

This is great news, and I’d like to offer my 2 cents on what an ideal mobile WordPress platform might look like. Because despite several attempts I haven’t been able to figure out a good workflow for publishing to WordPress from my iPhone or iPad.

Let’s take this post as an example. I read Matt’s article in Instapaper. I used the awesome “Create Note in Simplenote” feature to send the above quote to my preferred writing app. I am writing these words in Simplenote for iOS using Markdown. Writing down the words is a breeze; geting those words to my blog is a mission (and usually results in a big time delay). I’m going to wait until I get home, open my laptop, and wait for nvALT to sync with the text I entered into Simplenote. Then I’ll copy the Markdown into MarsEdit, add some URL and keyword specifics, and hit Publish.

The WordPress iOS apps are not helpful to me, because they don’t allow you to add custom fields and URLs. For example, for link posts I have a custom field that turns the title of the RSS entry for that post into a link that takes the reader directly to the original article. I can’t do that in the iOS app.

But here’s the thing – I don’t want a better WordPress iOS app. I don’t even want a mobile-optimized WordPress Dashboard. Instead, I want all the apps I already use to integrate seamlessly with the WordPress backend. So my ideal mobile WordPress experience is this: make it dead easy for text editor apps to publish to WordPress.

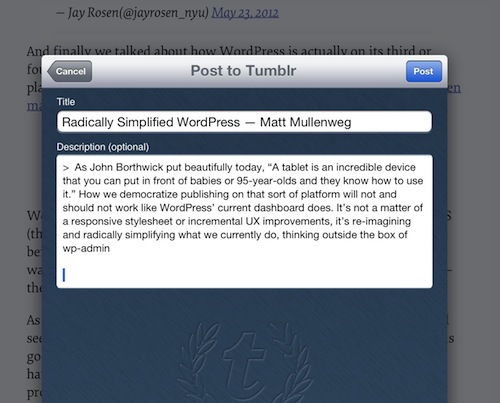

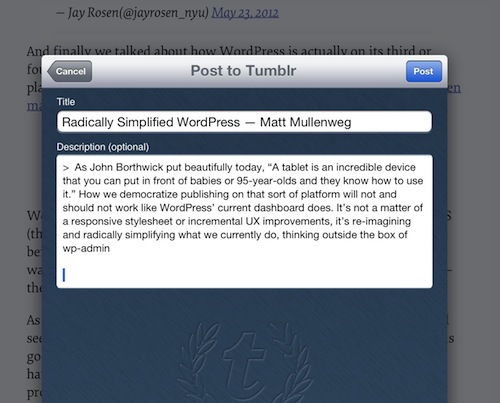

Once I’m done writing this post in Simplenote I would like to tap a link that says “Publish to WordPress.” I would then like to see a customizable dialog that lets me add/edit all the fields I have chosen to include, hit Post, and be done. It could work similar to Tumblr integration on Instapaper, except with customizable fields:

Maybe this is already what the WordPress team is thinking about – I certainly hope so. Either way, I know that this kind of seamless integration would truly free us to publish from anywhere, and will put a final nail in the coffin of the “iPad is only for consuming” argument.

It would be great to get more insight from the WordPress team on what they’re working on for mobile.