In Facebook threatens to ‘Zuck up’ the human race, Andrew Keen makes the following observation:

Sherry Turkle, Professor of the Social Studies of Science and Technology at MIT, tells us there’s a shift from an analog world in which our identities are generated from within, to a digital world in which our sense of self is intimately tied to our social media presence.

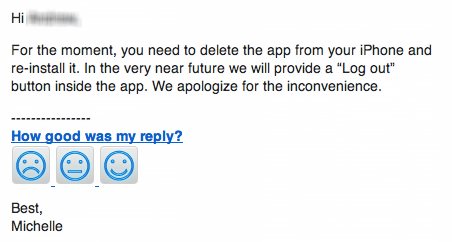

In other words, on Twitter and Facebook, we become who we follow. Or perhaps more accurately, we envy who we follow. The big problem with this is that none of us are really who we portray ourselves to be online. We are all the better, happier, more successful versions of ourselves:

(Source: Comical Concept)

But even though we take in all this information from people who we know aren’t real (and sometimes don’t even like), we are incapable of stopping. There is always more to know, more to discover, another person to compare ourselves to. In Noise and Signal, Nassim Taleb explains why this is so counterproductive:

The more frequently you look at data, the more noise you are disproportionally likely to get (rather than the valuable part called the signal); hence the higher the noise to signal ratio. And there is a confusion, that is not psychological at all, but inherent in the data itself. Say you look at information on a yearly basis, for stock prices or the fertilizer sales of your father-in-law’s factory, or inflation numbers in Vladivostock. Assume further that for what you are observing, at the yearly frequency the ratio of signal to noise is about one to one (say half noise, half signal) “” it means that about half of changes are real improvements or degradations, the other half comes from randomness. This ratio is what you get from yearly observations.

But if you look at the very same data on a daily basis, the composition would change to 95% noise, 5% signal. And if you observe data on an hourly basis, as people immersed in the news and markets price variations do, the split becomes 99.5% noise to .5% signal. That is two hundred times more noise than signal “” which is why anyone who listens to news (except when very, very significant events take place) is one step below sucker.

Most of the information we get on social media is not just noise, it also makes us less likely to discern between what’s important and what’s not. Greg McKeown explains in The Unimportance of Practically Everything:

Social media did not create the problem of distraction, but it is clearly an amplifier. Indeed, a study [PDF] by Clifford Nass et al. at Stanford showed that heavy media multitaskers are more susceptible to interference from irrelevant environmental stimuli than light media multitaskers. Heavy multitasking may encourage even heavier multitasking because it leads to a “reduced ability to filter out interference.” Could the part of our brain that is processing deeper cogitative thought actually be atrophying in the process?

None of this would matter if activity and reward were linearly related. But we live in a world where almost everything is worthless and a very few things are exceptionally valuable. This is a counterintuitive idea. After all, the idea that 50% of results come from 50% effort is appealing. It seems fair. Yet, research across many fields paints a very different picture.

As I read through these articles it became clear to me that most of us are not being very good stewards of our time and attention. We are seduced by the lure of constant affirmation that social media promises, and blind to the reality that what we mostly get from it is a sense that we’re not as good, happy, and successful as those around us.

We have a responsibility to ourselves to follow and interact with those who support us and want to make the world a better place. And we have an obligation to cull and surrender the people and the information that make us feel inferior and stunt our growth. This is difficult, because we’ll never get rid of our fear that we might be missing out on something. But it’s necessary if we want to hang on to our sanity and our ability to tell the vital from the trivial — so that we can continue to do good work.

Of course I can’t tell you what to do. But for myself, I’m going to start ignoring constant negativity, unimportant noise, and empty criticism. I’m actively going to seek out positive, driven people and honest critique. Nassim Taleb says it well at the end of his article:

To conclude, the best way to mitigate interventionism is to ration the supply of information, as naturalistically as possible. This is hard to accept in the age of the Internet. It has been very hard for me to explain that the more data you get, the less you know what’s going on, and the more iatrogenics (“an inadvertent adverse effect or complication resulting from medical treatment or advice”) you will cause.

Be careful who you listen to, because sooner or later, they end up defining you.