Most successful applications do a good job of onboarding users to teach them how the basics work. After that, good applications also make it easy to learn more advanced features simply through repeated use. You might make a wrong turn once, but if the application corrects your course, you never make that mistake again.

But sometimes there are features that fall between the cracks of onboarding and self-learning. It usually happens when there is some unique behavior in the app that is not only presumed to be commonly known by all users in the community, but is also small enough so that it’s not worth making a big deal out of during new user onboarding.

I recently thought of two such examples that I wanted to share, along with some suggestions for addressing the issue.

Twitter mentions

First, there is the issue of Twitter mentions. I still see people who I know have been on Twitter for years, who don’t know that if they start a tweet with “@”, not all their followers will see it. This information is buried deep in Twitter’s Help section, where I’m guessing very few people venture to. From Types of Tweets and Where They Appear:

Users will see @replies in their Home timeline if they are following both the sender and recipient of the update. Otherwise, they won’t see the @reply unless they visit the sender’s Profile page.

This is fairly clear, but if you don’t think about this as an issue, you won’t know to ask the question, so it’s not information you’re likely to seek out.

Instagram replies

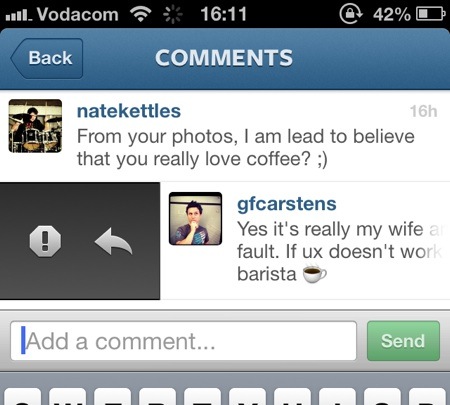

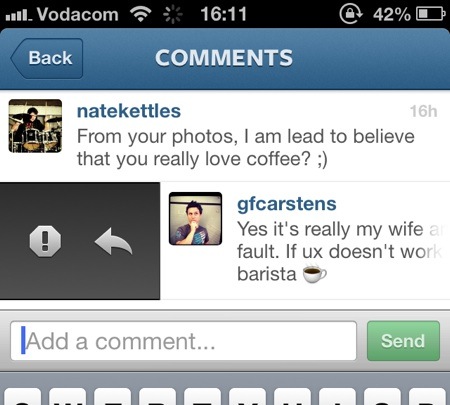

Second, there is replying to comments in Instagram, which I’m sure trips up quite a few people. If you comment on one of my photos in Instagram, I will get a notification. But if I respond to your comment without including your @username, you won’t get a notification. This is not how it works on Facebook, where you get notified of five comments after the one you posted1. Instagram does have an easy way to reply to people with their usernames, but it’s a slide gesture I discovered by accident:

So the easiest way to reply to someone is to slide from left to right on their comment, then tap on the arrow. Or you can start the comment with an @, which will then autocomplete the name as you type. But it’s not something they tell you about explicitly. It’s also, again, not information most people will seek out actively, since they’re getting notifications for each comment on their own photos, so why worry?

A proposal

My proposed solution for this type of situation is fairly simple. In the case of features that don’t behave as people expect them to, show a lightbox-type message to explain how it works just one time — the first time they perform the action. For example, the first time a user sends a tweet that starts with an @, show a message to explain who will see it. And the first time a user comments on one of their own photos in Instagram, show a message that explains when people get app notifications.

These are small but important details, especially for social services where understanding exactly what happens when you hit “Post” is essential to the enjoyment of the app.

Related post from the Elezea archive: Best practices for user onboarding on mobile touchscreen applications.