There’s certainly a lot of hand-wringing going on about Facebook Home. And although there is some truth to articles like Facebook Home — My Personal Hell and Why Facebook Home bothers me: It destroys any notion of privacy, I feel like making this story’s headlines about how boring Facebook is and how it’s just another step towards evil corporations owning all our data is missing out on what’s really important about this announcement. The much more interesting question is this: How does Facebook Home impact identity?

Perhaps the best analysis I’ve seen about Facebook Home is a tweet written by Rebekah Cox back in January 2011:

Rebekah expands on this in her post Mobile Identity, in which she concludes:

A mobile experience that truly represents your identity — in a way that both resembles and enhances an in-person conversation but still affords you control over how you portion out your attention and provides context — could tie the knot for the myriad communication channels available.

That certainly sounds like an accurate description of what Facebook is trying to do with this new product. Now add to that Dan Frommer’s analysis in Who’s Going To Buy The Facebook Phone?:

What about those millions of people who have bought Android phones who don’t really care that they’re Android phones, or even smartphones? […] My guess is that many — most? — of these people are Facebook users, and could easily see some utility in having Facebook features highlighted on their phones. And — bonus — Facebook’s software looks good. Much better than the junk that ships with typical low-end Android devices.

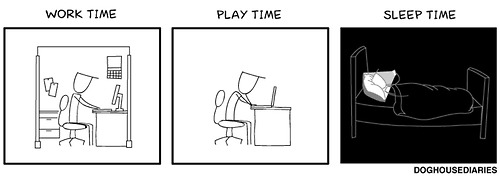

Put these two things together — identity and easy access — and Facebook’s strategy starts to become clear. For the majority of people life increasingly revolves around the Internet and their phones. This cartoon pretty much sums it up:

Image source: DOGHOUSE

It’s also clear that many people’s identities are getting tied up in Facebook. And Facebook is really good at accelerating the pace at which that is happening. Much has been written about Edgerank — the algorithm Facebook uses to decide what stories to show in people’s News feeds — and how it ends up promoting confirmation bias by only showing users stories that they are likely to agree with. Facebook knows the truth behind Clay A. Johnson’s words in The Information Diet:

Just as food companies learned that if they want to sell a lot of cheap calories, they should pack them with salt, fat, and sugar — the stuff that people crave — media companies learned that affirmation sells a lot better than information. Who wants to hear the truth when they can hear that they’re right?

What’s even more interesting about this is that Facebook is in the process of reversing a media trend that started with telegraphy. Before the introduction of the telegraph all news was local, and had a high “information-action ratio” — meaning that you could do something about what you read or heard about. But as Neil Postman points out in Amusing Ourselves to Death:

The telegraph made a three-pronged attack on typography’s definition of discourse, introducing on a large scale irrelevance, impotence, and incoherence. These demons of discourse were aroused by the fact that telegraphy gave a form of legitimacy to the idea of context-free information; that is, to the idea that the value of information need not be tied to any function it might serve in social and political decision-making and action, but may attach merely to its novelty, interest, and curiosity. […] Most of our daily news is inert, consisting of information that gives us something to talk about but cannot lead to any meaningful action.

Television and the Internet kept this trend going. All I have to do is say the word “Kardashian” and you’ll know what I mean. But Facebook — and particularly Facebook Home — is a return to “news that’s relevant”. Because it’s news about the people you have let into your life, and therefore news you can do something with (even if it’s just liking a status). Whatever your thoughts are on the privacy and sociological implications of Facebook as a service, you have to admit that it increases “information-action ratio” by (1) giving you information that’s relevant and (2) reducing the effort required to take some kind of action on that information1. That’s pretty powerful stuff.

What Facebook Home is really about

So, let’s tie all of this together. What Home allows Facebook to do is put Edgerank and people’s “social graphs”2 on steroids by giving them easy access to their identities. A Facebook-centric phone that constantly tells you what you want to hear about yourself and your friends means that you’ll find less and less use for the rest of the Internet. And that’s very, very good for Facebook since engagement is everything for an ad-based business.

Where does this leave us? I’m trying to reserve judgment about where this road that Facebook is paving will lead us. All I know is that they are doing some very smart things from a strategic business perspective. They are making news relevant again. They are shaping people’s identities (with a lot of help from Edgerank). And now they have found a way to go beyond apps and do a complete takeover of the device that most people never leave out of their sight.

Tech journalists can write about privacy and the virtues of quitting Facebook all day long. The rest of the world won’t even hear about it, because they’ll be too busy getting immersed in the lives and identities of the friends they agree with.