I get these weird obsessions sometimes—a thing that starts small in my head until it becomes all-consuming for weeks on end. Maybe you can relate? Anyway, my current obsession is centered around jazz, and how much we can learn from it about technology, how we listen to music, and yes, even design.

If you follow me on Twitter you’ll know that I just finished reading How to Listen to Jazz, a book I thoroughly enjoyed. I shared screen shots of some of my favorite sections from the book here, but suffice to say it is about so much more than jazz, and I highly recommend it not just for music lovers, but for anyone who works in a creative role.

Right on cue, as so often happens on the internet, I came across Ken Norton’s excellent post Please Make Yourself Uncomfortable, about some of the leadership lessons we can learn from great jazz records (especially the all-time best one, Kind of Blue):

Miles, Ella, and Duke were adept at guiding their bands into the optimal anxiety zone, making them restless and opening up a space where they could create masterpieces. Such talent is also needed in product management. So much of what we’ve learned, our instincts, are to do the complete opposite. We’re told to minimize risk, communicate a clear plan, and document every step. As product managers, our most important job is to help our teams find the place of optimal discomfort—the goldilocks zone of ambiguity and uncertainty.

The same day I read Gretta Harley’s The Slow Listening Revolution, about why she still has a vinyl collection:

Why vinyl? Commitment. In this mid-second decade of the 21st century, music is being taken for granted on a collective scale. An entire generation of music listeners will never pay for music, nor do they believe that they should. The long form music medium has taken a back seat to song culture, yet the average person only listens to a song for approximately 24 seconds before deciding if it’s worth their time to continue to listen. I ponder the substantive value of something that our capitalistic, corporate-model culture places on “free.” When we can listen to a whole song, or usually only 24 seconds of a song without paying for it, do we really value the music? I wonder if we listeners are as committed to music as we were pre-internet? I really like the internet, so these words are in no way a complaint or indictment, but merely observation.

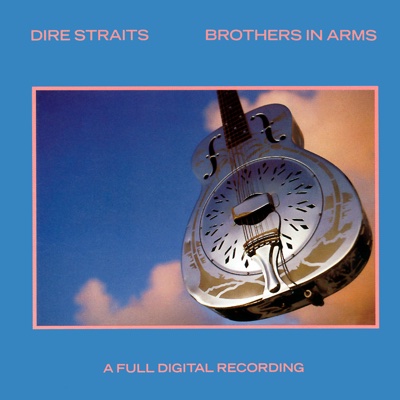

All of this—jazz, new music, old habits—came together as I picked up Dire Straits’s 1985 CD Brothers In Arms, which in some versions had this cover:

It used to be that proclaiming “A FULL DIGITAL RECORDING” was a selling point. Now, the first thing I look for when I buy an album is the phrase Mastered from the original master tapes, a sure sign of its 100% no-digital, analog-only experience.

Or, wait, maybe we’re just being anti-technology in our criticisms of digital music? There has always been a reluctance to adopt new things—a longing for the past and how things used to be. Clive Thompson gives us another example of this historical skepticism in That cursed newfangled technology, “electric lights”:

Robert Louis Stevenson penned “A Plea for Gas Lamps” in 1878, hoping to dissuade London’s authorities from installing obnoxious electric streetlamps like those in Paris. “A new sort of urban star now shines at night,” he wrote, “horrible, unearthly, obnoxious to the human eye; a lamp for a nightmare!”

So I don’t think we’ll solve this particular “which one is better” musical argument any time soon. But if history teaches us anything, it’s that it’s not a new argument, so we should just roll with it. And rock with it1.

-

Sorry, that’s a really bad joke. I’ll see myself out. ↩