A few years ago I almost went insane with commute-madness (which I’m reasonably sure is a thing). We lived in Bloubergstrand in South Africa, and I worked in the city of Cape Town. This meant that I had to be out of the house and on the road before 6am every morning (and leave work before 4pm), otherwise I would spend upwards of 90 minutes in traffic, as opposed to the more manageable (or so I thought…) 50-60 minutes.

It’s a little too soon for me to talk about the effect that commute had on my mental health, so I’ll just say this: I didn’t handle it well.

So I, along with thousands of my fellow commuters, rejoiced when the city of Cape Town extended the popular MyCiTi bus service out to where I lived. My joy was short-lived though. It turned out that even though they extended the bus line, the City decided not to provide parking nearby. So unless you lived within walking distance of the bus stop (which I didn’t) you were out of luck.

This seemed really silly to me, so I asked about it, and found out that the City didn’t want to provide parking until they could prove that the bus line was successful. It doesn’t take much to see the gigantic failure in logic here. The City didn’t want to provide parking until they could see that enough people used the buses, but not enough people can use the buses if there isn’t parking.

We ended up moving back to the city.

I tell this story because I recently got into a discussion with Vincent Hofmann, based on this tweet of his:

Cycle lanes in South Africa are a great idea but we’ll need orgs to get ready for healthier commuters with supporting infrastructure.

— Vincent Hofmann (@vincenthofmann) March 7, 2016

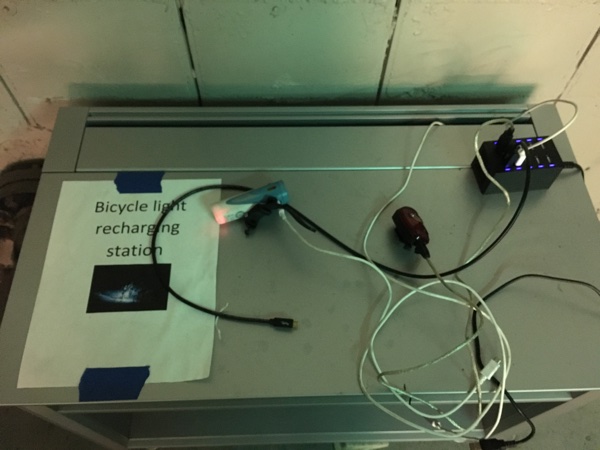

I brought up the MyCiTi thing, and then mentioned how different the experience is here in Portland, where I live now. I bike to work every day, and the only reason I can do that is that the end-to-end experience is designed well. It’s not just about the city installing bike lanes. Neighborhoods have to agree to stricter traffic rules. Companies need to provide facilities for safe bike parking and showers. It’s a collaboration between public and private sectors across the city. If anyone doesn’t pull their weight, the whole thing falls apart.

Luckily, in Portland, it all hangs together really well. Here are some photos of my end-to-end biking experience in Portland:

There is, of course, a big product management lesson here. We often spend so much time trying to perfect the experience people have with our products online, and we forget about what happens before and after they get there. And that’s often where the experience breaks down and we lose customers. As an example, I mentioned in my newsletter over the weekend how frustrating it can be if you can’t contact a company after making a purchase:

It sounds obvious, but it is still amazing to me how many companies see support as a liability. Any opportunity to interact with customers is a good thing. Yes, it’s expensive, and “case deflection” is a very effective way for companies to cut costs, but at what cost? A case deflected—either through finding the answer on a forum, or a customer simply giving up when they can’t figure out how to contact the company—is a missed opportunity to build loyalty and get input on your products.

And this, ultimately, is why customer journey mapping is such an essential activity for any product. It forces us to think about designing the end-to-end experience, from long before people get to our site, until long after.

Evidence of the danger of only focusing on the product experience itself is all around us—just look at the way our cities design public transport and bike commutes. Notice the differences between the two examples I shared above—one set up for failure, the other for success. And let that be a challenge to all of us to think about how people experience our products even when they’re not using our products.