This isn’t a zombie blog1. Still, I’d be doing you a huge disservice if I didn’t tell you about two excellent zombie books I read recently. The books are great because yes, they have zombies in them, but they’re not actually about zombies. They’re about how humans treat each other when we turn on each other. How it’s easy to speak about our values but a bit harder to stick to those values when the going gets really tough. And that’s a topic worth exploring.

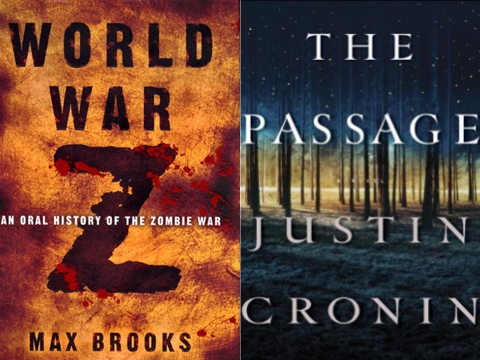

The first book I want to recommend is World War Z. The BOOK, not the movie! I saw the movie, and it’s fine, but it is not even remotely similar to the book. I don’t even know why they kept the title. It’s really strange. You should still see the movie, because it’s fun, but the book is something completely different. It is, as the subtitle promises, “an oral history of the zombie war”. The war happened. It’s over. This is a book about people reflecting on what went down. And it is fascinating.

There are commentaries about the media:

The only rule that ever made sense to me I learned from a history, not an economics, professor at Wharton. “Fear,” he used to say, “fear is the most valuable commodity in the universe.” That blew me away. “Turn on the TV,” he’d say. “What are you seeing? People selling their products? No. People selling the fear of you having to live without their products.” Fuckin’ A, was he right. Fear of aging, fear of loneliness, fear of poverty, fear of failure. Fear is the most basic emotion we have. Fear is primal. Fear sells. That was my mantra. “Fear sells.”

There are commentaries on what happens when “knowledge work” is not needed any more:

You’re a high-powered corporate attorney. You’ve spent most of your life reviewing contracts, brokering deals, talking on the phone. That’s what you’re good at, that’s what made you rich and what allowed you to hire a plumber to fix your toilet, which allowed you to keep talking on the phone. The more work you do, the more money you make, the more peons you hire to free you up to make more money. That’s the way the world works. But one day it doesn’t. No one needs a contract reviewed or a deal brokered. What it does need is toilets fixed. And suddenly that peon is your teacher, maybe even your boss. For some, this was scarier than the living dead.

And what happens when those workers relearn how to do stuff with their hands:

It gave people the opportunity to see the fruits of their labor, it gave them a sense of individual pride to know they were making a clear, concrete contribution to victory, and it gave me a wonderful feeling that I was part of that. I needed that feeling. It kept me sane for the other part of my job.

And finally, on freedom:

Freedom isn’t just something you have for the sake of having, you have to want something else first and then want the freedom to fight for it.

The deep thought that went into this book results in an engrossing story full of detail that makes you think about your everyday relationships, and what might happen if those relationships are strained beyond their limits. I loved it.

The second book is The Passage. First, the backstory is great. The author first began developing his ideas for the book when his daughter asked him to write a book about a “girl who saves the world.” Well, it’s about a girl, and she tries to save the world, but it’s like no hero story you’ve read before. It starts when the zombie apocalypse picks up steam, and then jumps ahead 100 years to focus on how one isolated community is dealing with the aftermath. In contrast to World War Z, the war is very much not over in The Passage. It’s gruesome at times, but again, beautifully written.

From interesting reflections on what zombies represent:

What were the living dead, Wolgast thought, but a metaphor for the misbegotten march of middle age?

To what it means to believe in the future:

A baby wasn’t an idea, as love was an idea. A baby was a fact. It was a being with a mind and a nature, and you could feel about it any way you liked, but a baby wouldn’t care. Just by existing, it demanded that you believe in a future: the future it would crawl in, walk in, live in. A baby was a piece of time; it was a promise you made that the world made back to you. A baby was the oldest deal there was, to go on living.

And the nature of hope:

Courage is easy, when the alternative is getting killed. It’s hope that’s hard.

The Passage is not just a great story (I couldn’t put it down), but also another interesting look at what happens when circumstances bring out the worst (and the best) in humans.

All this got me thinking again about an article I read recently about the Zombie Renaissance in literature. And I realised how true this part is about these two books:

We are living in a time when what counts as “life” is in significant scientific dispute, and in the heyday of zombie computers and zombie banks, zombie this and zombie that. Why wouldn’t we also be living in a time of zombie literary forms? Whatever their specific emphases and intricacies, all these zombies represent a plague of suspended agency, a sense that the human world is no longer (if it ever was) commanded by individuals making rational decisions. Instead we are witnessing a slow, compulsive, collective movement toward Malthusian self-destruction. Of course all monsters are projections of human fears, but only zombies make this fundamentally social and self-accusatory charge: we the people are the problem we cannot solve. We outnumber ourselves.

If this is an idea that interests you, I highly recommend these books. Even if you don’t like zombies, you’ll appreciate the thoughtful writing and gripping stories. Do it.

-

Although, maybe a pivot is in order? I’ll think about it. ↩