Content strategy is starting to get its much-deserved time in the spotlight as part of the user experience design family. As basic examples of confusing/bizarre content like this one and this one show, getting serious about content is way overdue. But I’m a little worried that we haven’t seen much talk on how to measure the effectiveness of web content. It is unfortunate that in some companies it is still a struggle to sell the benefits of UX design, but it is the reality, so we have to deal with it.

Selling content strategy to clients and stakeholders is, of course, not the only reason why measuring its effectiveness is important. It is also essential as part of the whole design process:

- How do we select the best content if we have a variety of different alternatives, each with its own group of supporters who want to get it on the site right away?

- Since the voice of a web site can be such an abstract, arbitrary decision sometimes, how can we apply methodologically robust research methods to help make these decisions?

- How do we know that the content we wrote made a difference on the site?

So that is what this post is about — a proposal for how to measure the effectiveness of web content.

What makes content effective?

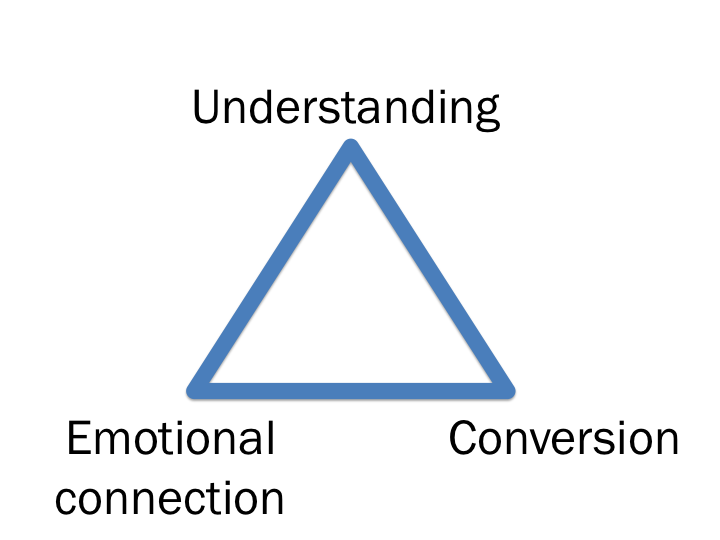

First, I would define “effectiveness” in this context as the optimization of the following three concepts:

- Do users understand what you are trying to tell them and what action they should take to be successful in their task?

- Are you invoking the desired emotions with your content?

- Does the proposed content result in higher conversion rates than other alternatives?

It’s so important to combine the user perception data (the first two concepts) with business metrics (the third concept). From my experience the only way for user experience designers to affect change is if we can show the positive impact these changes have on engagement/revenue metrics.

Measuring content effectiveness

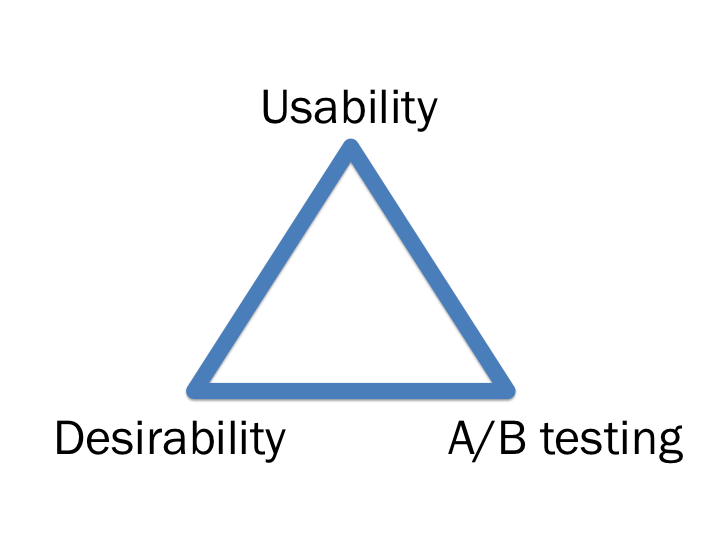

My proposal is to map each of the three concepts to a research methodology that is specifically designed to get the needed information:

Each of the three methodologies can be used to measure the effectiveness of different versions of the same content before it goes live, as well as measure what difference it makes once it is live. This is also a really nice way to progressively reduce the number of alternatives down to the best solution.

I’ve written about usability testing and A/B testing before so I’m not going to go into more detail on that, but I do want to spend a little time on Desirability testing since it’s a method I really like, and I think it’s not used enough to measure design/content effectiveness.

Desirability testing

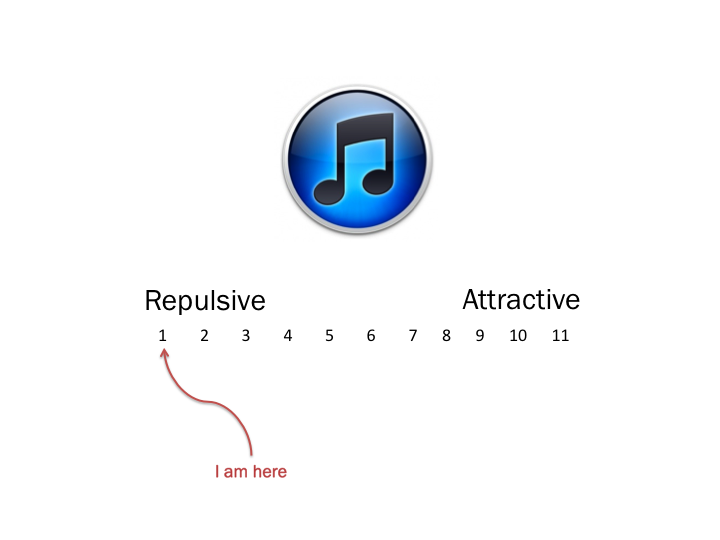

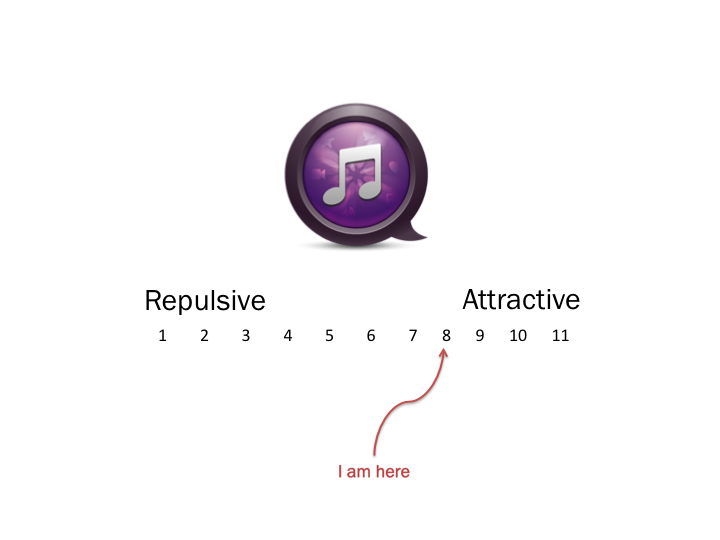

In desirability testing, a survey is sent to a large number of users where they are asked to rate one of the proposed design/content alternatives using a semantic differential scale. The survey is done as a between-subjects experiment, meaning each user sees only one of the proposed designs, so that they are not influenced but the other design alternatives. The analysis then clearly shows differences in the emotional desirability of the proposed alternatives.

So, for example, you could show one group a design and ask them how they feel about it:

And then show a different group another image and ask them the same question:

When you then compare the averages of the different groups, you’re able to make an accurate relative comparison between the two designs.

Putting it all together

In summary then, to apply all of this to measuring the effectiveness of content:

- Usability testing. Start with several different version of the content (~10), along with the current version (if it exists). Ask users in a lab setting what they understand the content to mean, and any other thoughts they have on the way it sounds. This should help narrow down the alternatives to 4-6 possibilities.

- Desirability testing. Use the Desirability method in a large sample online survey as a between-subjects experimental design. In the survey, ask users to rate the content on different brand and design attributes. This way you can determine what emotional response the content elicits from users. You’d also be able to ask users which version of the content they’d prefer, and why. This method has the added benefit of large numbers to give you confidence in the statistical significance of the results.

- A/B testing. Once you’ve narrowed the alternatives down to two or three, live A/B testing can help you determine which of the alternatives perform better from a revenue or engagement perspective, by looking at differences that can be attributed purely to content changes. This obviously works easiest when the content is directly related to a revenue-generating task, like the call to action on a checkout page, for example. But it’s not just about revenue — there are great ways to measure metrics of engagement with the page, which is just as powerful.

Now, I can see a few issues that make this a pretty difficult task, and it’s the reason why the above three methods should not be used in isolation. In combination, they help tell the whole story.

- It is difficult to know what users really read on a page. In the first two methods you pretty much have to show people what to read — that doesn’t happen when they visit your site organically with no one looking over their shoulder. This is why A/B testing is so important as it gives you a sense of how behavior will change based on content.

- It is difficult to isolate the effect of content changes from the other influencing factors on a page. This is the really difficult part. How do you know that conversion/engagement improved because of the content and not of some other factor on the page, like visual design changes? That is why it is important to keep the rest of the page exactly the same, and also why usability and desirability testing is important to bring out the perceptual data from users.

- [Update] This method doesn’t scale well. When you are doing a major redesign or re-write, you can’t do this for every single change (as Eric Reis points out in the comments of this post). The method is mostly suited for microcopy and incremental improvements once the base content has been written.

And the biggest problem is of course that this is an idealistic approach. Finding the resources/time/money to do this for every content change is obviously not feasible. But for high-value landing pages, in-line help, etc. this approach could be well worth the investment.

This is also by no means the only way to measure content effectiveness, but I think it’s a good approach that balances methodological rigor with the dangers of not overdoing it. I’d be curious if anyone has any thoughts or ideas on how to improve on this proposal.

PS. Last week I discussed this topic at the first Cape Town Content Strategy meetup. I uploaded the slides here, and you should join the Cape Town group here.